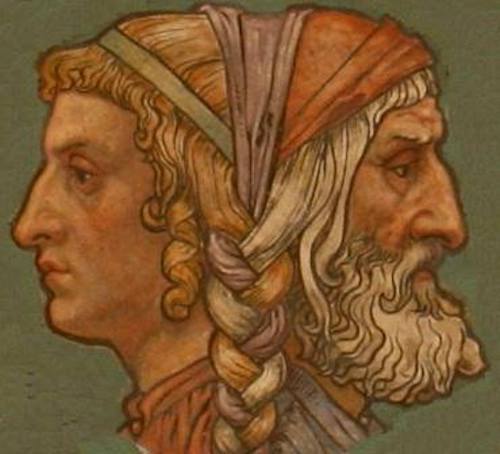

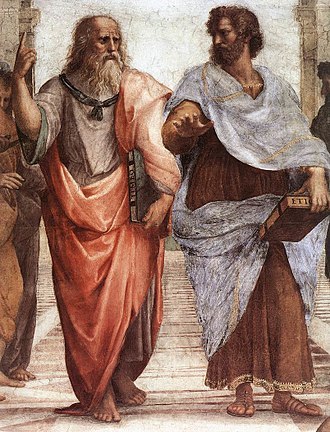

We have seen that Aristotle opposed Plato and the Pythagoreans on the question of reincarnation, while the Gnostics agreed but reversed the meaning. Today I want to look at another anti-reincarnationist viewpoint-- that of the orthodox Church Fathers.

The Reward of the BodyDionysius the Areopagite, in his treatise on the

Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, tells us the following, in the passage concerning the rites said over those who have died:

The holy souls, which may possibly fall during this present life to a change for the worse, in the regeneration, will have the most Godlike transition to an unchangeable condition. Now, the pure bodies which are enrolled together as yoke-fellows and companions of the holy souls, and have fought together within their Divine struggles in the unchanged steadfastness of their souls throughout the divine life, will jointly receive their own resurrection; for, having been united with the holy souls to which they were united in this present life, by having become members of Christ, they will receive in return the Godlike and imperishable immortality, and blessed repose.

Of the idea of reincarnation he has this to say:

But others assign to souls union with other bodies, committing, as I think, this injustice to them, that, after (bodies) have laboured together with the godly souls, and have reached the goal of their most Divine course, they relentlessly deprive them of their righteous retributions.

Dionysius was a thoroughgoing Platonist, hardly ignorant of the tradition of reincarnation. The passage cited here is derived in large part from Plato's Phaedo. Another treatise, the Divine Names, is concerned (as one might expect) with the Names of God given in the scriptures and elsewhere in the Christian tradition. The first name that he cites is Goodness, and his discussion of it is derived directly from Plato's Republic:

Even as our Sun-- not as calculating or choosing, but by its very being, enlightens all things able to partake of its light in their own degree-- so too the Good-- as superior to a Sun, as the archetype par excellence, is above an obscure image-- by Its very existence sends to all things that be, the rays of Its whole goodness, according to their capacity.

And again:

The Good then above every light is called spiritual Light, as fontal ray, and stream of light welling over, shining upon every mind, above, around , and in the world, from its fulness, and renewing their whole mental powers, and embracing them all by its over-shadowing; and being above all by its exaltation; and in one word, by embracing and having previously and pre-eminently the whole sovereignty of the light-dispensing faculty, as being source of light and above all light, and by comprehending in itself all things intellectual, and all things rational, and making them one altogether.

And so we see that Dionysius is informed from his very first principles by the Platonic tradition. And yet, in this passage alone, he appears to directly attack Plato himself. Why?

Why Bother with the Other Philosophers?

Dionysius was one of the most important of the early theologians. He retains his status in the Christian East, wherein he is often still venerated as Saint Dionysius, the companion of Saint Paul. In the West Dionysius's influence is today felt more indirectly, via his influence on Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas draws heavily on Dionysius, citing him 1700 times. But Aquinas is above all an Aristotelean-- he loves Aristotle enough that he refers to him as "The Philosopher." Of Plato he has a much lower opinion. In this Aquinas represents a deviation from the earlier, dominant, Christian tradition, and that deviation has affected Western Christianity down to the present. But let us leave that discussion for another time.

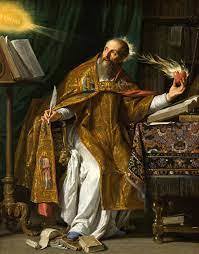

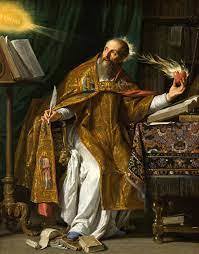

Writing many centuries before Aquinas, Augustine of Hippo is far more in line with what I'm calling the Christian mainstream. Several books of his City of God are addressed directly to the Platonists of his day, specifically because,

as he says, of all the pagan philosophers, "It is evident that none come nearer to us than the Platonists." Indeed, he has a great deal of praise for Plato himself and for the philosophical system which bore his name:

If, then, Plato defined the wise man as one who imitates, knows, loves this God, and who is rendered blessed through fellowship with Him in His own blessedness, why discuss the other philosophers?

Through several books Augustine elaborates the doctrines of the Platonsits of his day, and their differences with the Christians. In Book X, he comes to the subject of reincarnation, as part of a long discussion of Porphyry:

It is very certain that Plato wrote that the souls of men return after death to the bodies of beasts. Plotinus also, Porphyry's teacher, held this opinion; yet Porphyry justly rejected it. He was of opinion that human souls return indeed into human bodies, but not into the bodies they had left, but other new bodies. He shrank from the other opinion, lest a woman who had returned into a mule might possibly carry her own son on her back. He did not shrink, however, from a theory which admitted the possibility of a mother coming back into a girl and marrying her own son. How much more honorable a creed is that which was taught by the holy and truthful angels, uttered by the prophets who were moved by God's Spirit, preached by Him who was foretold as the coming Saviour by His forerunning heralds, and by the apostles whom He sent forth, and who filled the whole world with the gospel, — how much more honorable, I say, is the belief that souls return once for all to their own bodies, than that they return again and again to various bodies? Nevertheless Porphyry, as I have said, did considerably improve upon this opinion, in so far, at least, as he maintained that human souls could transmigrate only into human bodies, and made no scruple about demolishing the bestial prisons into which Plato had wished to cast them. He says, too, that God put the soul into the world that it might recognize the evils of matter, and return to the Father, and be for ever emancipated from the polluting contact of matter. And although here is some inappropriate thinking (for the soul is rather given to the body that it may do good; for it would not learn evil unless it did it), yet he corrects the opinion of other Platonists, and that on a point of no small importance, inasmuch as he avows that the soul, which is purged from all evil and received to the Father's presence, shall never again suffer the ills of this life. By this opinion he quite subverted the favorite Platonic dogma, that as dead men are made out of living ones, so living men are made out of dead ones; and he exploded the idea which Virgil seems to have adopted from Plato, that the purified souls which have been sent into the Elysian fields (the poetic name for the joys of the blessed) are summoned to the river Lethe, that is, to the oblivion of the past,

That earthward they may pass once more,

Remembering not the things before,

And with a blind propension yearn

To fleshly bodies to return.

Reincarnation, Incarnation, Resurrection

Augustine and Dionysius have their differences. Above all, from my own perspective, I find Dionysius's writings inspiring, and his vision compelling; I don't think that Dionysian Christianity is, ultimately, correct-- but for spiritual sustenance, from my own perspective, it would be sufficient. Augustine is harsher, more given to disputation; I frequently find him unpleasant, sometimes downright appalling. Here he is describing the fate of unbaptized babies:

Let no one promise infants who have not been baptized a sort of middle place of happiness between damnation and Heaven, for this is what the Pelagian heresy promised them.

Yes, he's saying what you think he's saying. For Augustine, an infant who dies before baptism is consigned to Hell. And yes, that includes babies who die in the womb. I will return to this subject in due time.

For now, what I want to note is the specific vision of human life and the human soul that unites both Augustine and Dionysius, and separates them from Plato, or from his later successors like Plotinus and Porphyry.

For Plato, just as Augustine says, "The living come from the dead, and the dead from the living." Now, Augustine makes it "a favorite doctrine of the Platonists" that this is the case for all human souls-- that is, that we are all subject to reincarnation, for all of time. Porphry and Plotinus did not believe this; for them, the souls of those who are purified return to the Intelligible Realm, and abide there eternally. It was, however, the teaching of Proclus, and of his school-- which some have identified as an "Eastern" school of Platonism, as opposed to the Western school of Plotinus et al-- more generally. Where Plato stood on the subject depends on which dialogue you are reading, as do many such details. Unlike his later followers, Plato appears to have been happy to keep certain questions open.

Whether or not they believed that human souls would eventually return to material incarnation, the Platonists were united in believing three things: First, that our souls are eternal; second, that they begin their existence in the presence of God, and strive to return to him; third, that the journey of the soul's return to God takes place across many lifetimes.

The differences between Augustine and Dionysius are certainly as great as those between Plotinus and Proclus, but they, too, are united by their underlying beliefs about the soul and its relation to body, which can also be described as consisting in three principles: First, our souls are created by God and come into existence with our bodies; second, upon death, our soul departs the body either into the presence of God, or not; third, at the end of time our soul and its body will be reunited.

It is true that, as Augustine says, the Platonists are the closest to the Christians of all of the ancient philosophical schools. Both traditions believe in a single Creator; both believe that moral action in this life determines our fate fater death; both believe that the purpose of the soul in this life is to return to God. Describing the nature of the life of God (

City of God, Book VIII), Augustine speaks for both the Christians and the PLatonists when he says:

And therefore, whether we consider the whole body of the world, its figure, qualities, and orderly movement, and also all the bodies which are in it; or whether we consider all life, either that which nourishes and maintains, as the life of trees, or that which, besides this, has also sensation, as the life of beasts; or that which adds to all these intelligence, as the life of man; or that which does not need the support of nutriment, but only maintains, feels, understands, as the life of angels — all can only be through Him who absolutely is.

Where they differ, and differe greatly, is in what they see as the nature of the human person and its relationship to the physical world.

For the Platonists, the soul has a body, just as a body has clothes. In the same way that our body changes clothes, our soul changes bodies. Just as our body is sometimes naked, so, too, our soul is sometimes naked. And when the soul is naked-- that is, not in a body-- this isn't a loss, or a condition of deprivation. The soul between lives abides in the spiritual world, in a pleasant or a painful part depending on its merits. After its long sojourn through the realms of earthly existence-- including those parts of the spiritual world which are the abodes of the human Dead-- it returns to the Father and rests in the Intelligible Realm, either forever or until time begins again.

For the Christians-- at least, the mainstream Christians-- the soul and the body are, essentially, one. In this, the Christian doctrine far more closely resembles that of Aristotle, who we looked at last time, and you will often hear Christians both Western and Eastern citing Aristotle on this topic. The soul no more "has" a body than Architecture "has" schools or drawing boards or architects. To imagine Architecture deprived of its instruments, or in possession of different instruments, would simply be to imagine a different art entirely. Similarly, on this account of soul and body, to possess a different body would be simply to be someone else. Death, on this account, is a disaster; and, indeed, Christianity sees Death as the result of the Fall. Prior to Adam and Eve's expulsion from Paradise, they were ensouled bodies who did not die; after the Fall, the monstrous absurdity that is the separation of soul from body became possible. But, on this account, all will be corrected in due time.

I know that I find one of these accounts far more plausible than the other, and readers of this blog will already have guessed which one. Before we get to that, though, I want to discuss one more alternative take on the subject. We'll get to that tomorrow. Or next time.