Rushing to work today to make an 11:30 appointment, I looked down at my phone to make sure I had the time correct and discovered that the appointment had been canceled sometime between the time I left the house and that moment. And, looking at my phone, I managed to miss my exit, and drove some 20 more minutes into the mountains of Western Virginia before realizing what I had done. I now find myself sitting at a coffeeshop in a place called Purcellville, with several hours to kill, or to use.

And so I'd like to take the opportunity to discuss something that's frequently on my mind, which is the question of how we ought to read Plato's political writings, and what relevance they have to our modern politics.

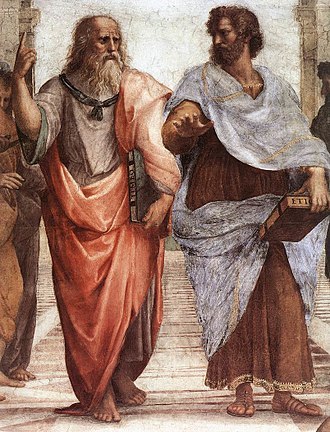

Plato and Politics

Modern treatments of Plato very often take him as some sort of weird old politician. In College I was forced to read the Crito in a Political Philosophy class, and told nothing of its author except that he was very old and very dead, but that we ought to know something about what he had thought on political topics merely as a way of saying "People have been talking about these matters for some time now."

Plato does indeed discuss politics-- or, rather, law-- in the Crito, but he treats of political matters much more fully in the Republic, the Statesman, and the Laws, three dialogues which come out to nearly 700 pages between them. As my own copy of the Complete Works of Plato comes out to around 1700 pages, these 3 dialogues between them make up some 40% of the entire body of Plato's work. Since Platonism has become so central to my thinking and to what I'm trying to do with this blog and my work in general, I thought it was worth spending some time on this issue.

In this post, I'd like to give an overview of Plato's political views, discuss how we ought to approach Plato's politics and what relevance they have to our approach to Platonism as a spiritual discipline, and, finally, to see whether Platonic politics has any relevance to our modern world.

Before we do that, though, it is critical that we understand what "politics" means in Plato's world.

The PolisThe word "politics," as you probably know, is derived from "polis," which is the ancient Greek word for a city. And, as you probably also know, the Greek world was composed of city-states, which were countries so small they were limited to a single city. This is what I was taught, at any rate, and if you know any better than this you're further along than I was just a short while ago.

It is true that the political unit Plato was discussing was the polis and it is true that the polis is a city and that the reach of a particular government in ancient Greece did not extend beyond the reach of a particular polis. But matters are not as simple as that. The polis, you see, is not simply a smaller version of one of our modern states, nor is the government of a polis the equivalent to the US Congress on a smaller scale, or to the government of the town in which you live. The polis is not merely a smaller thing than the things that we have, it is a different kind of thing altogether.

The best book on this subject is

The Ancient City, by a Frenchman named Fustel Coulanges; you ought to read the whole thing when you have a moment. In The Ancient City, Coulanges shows that, in the "cities" of the ancient world, the categories of human life that we currently separate under the headings "family" "religion" and "government" were not separate, but were a single category of experience called "the city" or "politics."

To illustrate how such a thing is possible, let's think about it in reverse. In our society, the life-categories "marriage" "child-rearing" and "residence" are combined under the single heading, "family." A "family" consists, ideally, of a married couple, sharing a home, and raising their children. To us, nothing in the world could be more natural; even where this system breaks down, it is still there in the background as something which is missed.

Imagine if we separated these things. Imagine a society in which husbands and wives don't live together-- the men live together with their friends and brothers in a dormitory or fraternity house, while the women have their own sorority, along with the youngest children. It's not that they don't get married-- they do. Husbands and wives go on dates and spend time together and sneak off into out of the way corners of town when they need some adult time. But they don't share a bed, and they don't share a house. And they don't raise children together-- the babies and young girls live with their mothers, yes, but men don't even raise their own sons. Instead, they raise their sisters' sons. When boys come of age, they are sent to live in their uncle's fraternity house, which is invariably in another city, since women move to a sorority house attached to their husband's fraternity, and it's considered somewhat incestuous to marry a girl from your home town. If a boy lacks an uncle, a suitable male relative is found for him, back in the mother's hometown-- but never his father.

Does that sound odd, or impossible? In fact, it's a very common social arrangement among certain tribes of the New Guinea highlands. So yes, it's very possible.

Now let us suppose that a similar living arrangement is found among our own descendants living right here in America sometime around the year 4500. Categories of life that seem to us to be obviously connected seem to them to be completely separate. Moreover, just as we pride ourselves on having separated the categories of "religion" and "government"-- and both from "family"-- much of their identity as a people and a culture revolves around their having had the wisdom to separate residence from marriage and marriage from child-rearing.

Given such a set of circumstances, what would our descendants make of a modern philosopher who wrote at length about spiritual issues, but regularly connected them with the family-- an institution which they either no longer had, or no longer had in the same form? If a modern philosopher-- I give no examples as I don't know that there is one-- wrote several books of detailed advice on household-management, describing the proper roles of father, mother, and children, but also filled them with detailed discussions and hints and allegories of a grand and universal spiritual system, what could these descendants of ours do with it? Dismiss it out of hand? If so they would lose an enormous contribution to human wisdom and human excellence, as well as (let us imagine) the root of many of their own ideas. But if they attempted to adopt our philosopher's recommendations as far as household management whole-cloth, they would need to burn their own civilization to the ground and start again from scratch. And even if they managed it-- as they probably wouldn't-- it would be at the cost of an enormous amount of suffering and death. And they probably wouldn't manage it; they'd probably just get a lot of people killed.

This, I argue, is precisely the position that we are in with regard to Plato's political writings. The polis that he wrote of does not exist, and the concepts that applied to it cannot be applied to our modern governments, as modern government-- this is critical--

is not the heir to the polis.

The Fire, the House, and the King

Let's go back and discuss ancient society, drawing, again, on Coulanges.

The basic unit of that society is the

fireplace.

The fireplace? How is that possible?

In the ancient world the fire was-- as it still is today in India-- the living body of a god, or-- in the West-- a goddess, named Vesta at Rome and Hestia in Greece. Fire is a living being, and the fireplace-- the sacred hearth-- is a sacred altar. Every home has its fire, and lacking its fire, it is no home at all. The father, as head of the family, is also the high-priest of the religion of the hearth-fire. At the fire-- tended by his wife, the priestess-- the sacrifices are made every day to the spirits of the ancestors, the land on which the family lives, and the home in which they dwell. Sacrifices are made, too, to be sure, to the high gods and heroic ancestors that the family shares with its neighbors and its community as a whole, but at the microscopic level, each household is essentially a church and each family has its own, independent religion.

And each family is also a kind of political unit, with the father as its king.

In The Statesman, Plato discusses the nature of what he calls the True King, which is a leader who possesses the Science of Rulership. It's worth noting that, in the school of Iamblichus, The Statesman was read after The Sophist but before Philebus. In The Sophist, Plato discusses the nature of charlatan-philosophers called sophists, but the later Platonists understood him to also be discussing a being called the "Sublunar Demiurge," who is the trickster-god that creates the world that we experience with our senses, the exact equivalent of the Hindu Maya. The Philebus, meanwhile, is a discussion of the nature of the Good, which is the First God and Highest Principle. The Statesman must, therefore, also be understood as a dialogue about the nature of God Himself-- that is, the God that creates and governs the cosmos as a whole.

In the Statesman, Plato is explicit about the relationship between rulership of a city and rule of a household:

Stranger: Are we, then, to regard the statesman, the king, the slavemaster, and the master of a household as essentially one though we use all these names for them, or shall we say that four distinct sciences exist, each of them corresponding to one of the four titles?

....

Stranger: The science possessed by the True King is the Science of Kingship?

Socrates: Yes.

Stranger: The possessor of this science, then, whether he is in fact in power or has only the status of a private citizen, will properly be called a "statesman" since his knowledge of the art qualifies him for the title whatever his circumstances.

Socrates: Yes, he is undoubtedly entitled to that name.

Stranger: Then consider a further point. The slavemaster and the master of a household are identical.

Socrates: YEs.

Stranger: Furthermore is there much difference between a large household organization and a small-sized city, so far as the exercise of authority over it is concerned?

Socrates: None.

Stranger: Well, then, our point is clearly made. Once science covers all these several spheres and we will not quarrel with a man who prefers any one of the particular names for it; he can call it royal science, political science, or science of household management.

Layers of MeaningAll of Plato's dialogues were understood to have multiple layers of meaning. The Statesman is about the Science of political leadership, but it is also about how God rules the universe. The Republic, meanwhile, is supposedly a discussion of the ideal city, but Plato is explicit at the beginning of the dialogue that the city in quetsion is intended as an allegory of the soul:

Suppose [Here Socrates is speaking] that a short-sighted person had been asked by some one to read small letters from a distance; and it occurred to some one else that they might be found in another place which was larger and in which the letters were larger --if they were the same and he could read the larger letters first, and then proceed to the lesser --this would have been thought a rare piece of good fortune.

Very true, said Adeimantus; but how does the illustration apply to our enquiry?

I will tell you, I replied; justice, which is the subject of our enquiry, is, as you know, sometimes spoken of as the virtue of an individual, and sometimes as the virtue of a State.

True, he replied.

And is not a State larger than an individual?

It is.

Then in the larger the quantity of justice is likely to be larger and more easily discernible. I propose therefore that we enquire into the nature of justice and injustice, first as they appear in the State, and secondly in the individual, proceeding from the greater to the lesser and comparing them.

SummarizingLet's summarize our argument before we proceed. Two major issues have emerged:

1. The polis of Plato is not a smaller form of a modern state. It is, rather, a different form of social organization, in which the categories of life that we currently separate under the headings "family," "religion," and "government" are combined. Plato's political arguments, therefore, cannot be applied to our current forms of government on a one to one basis.

2. Plato's political writings, like all of his writings, admit of more than one reading. What appears to be a discussion of an ideal ruler of a city can also be understood either as a description of God in his government of the universe, or as advice to the individual concerning the care of his own soul, which is regularly likened to a state with workers, soldiers, and leaders.

The Heir to the PolisLet's consider the first issue.

Given the foregoing, the questions become: Do Plato's political theories have any applicability to our modern world as political theories? And, if so, can they be understood as applying to government, or are there other structures or organizations which might better be understood as heirs to the ancient polis?

Now, to a real extent, this is where we leave the domain of Truth and enter into the realm of Opinion. There are no fixed answers to these questions, and certainly Plato himself could not have anticipated them and gives no explicit guidance concerning them. So the following can only be my own view of hte topic.

That said, it's my view that Plato's writings on politics-- especially the three dialogues mentioned-- are very important, and very worth reading. But in a modern context, and perhaps especially in an American context, they have only minimal applicability to government as such. They work far better when applied to the lives of other heirs to the polis, including individuals and families, but also what are often called "civil society" organizations-- which can include anything from a church to a charity to a bowling league.

To illustrate what I mean, let's take another example from the Statesman, since it's currently open in front of me.

Toward the end of the dialogue, Plato describes the ways in which different virtues can be opposed to one another. Courage and Moderation, in particular, frequently come into conflict. Moreover, particular individuals often exhibit one personality type or the other, and these individuals then come into conflict. This leads to the ruin of hte state if individuals of either one type or hte other predominate. A state overrun by individuals of hte courageous type will be forever looking for conflicts with its neighbors, until it eventually antagonizes a larger power or a coalition of smaller powers and is overrun. A state dominated by the moderate type, meanwhile, will not fight even when it is necessary, and will soon find itself enslaved by its enemies. The wise statesman weaves together both types of individuals, so that they strengthen one another, allowing the state to fight or to make peace as necessary.

So far, this actually does seem like rather good advice as far as modern statecraft goes, even up to the level of global powers like the US and Russia.

But in the next part, Plato strays well beyond what is possible for any modern government. Having described the sort of education that unites the moderate and courageous types as the "divine link" between them, he now sets out to describe how to link them on the human level:

Socrates: But what are these links and how can they be forged?

Stranger: They are forged by establishing intermarriage between the two types so that the children of the mixed marriages are so to speak shared between them and by restricting private arrangements for marrying off daughters. Most men make unsuitable matches from the point of view of the betting of children of the best type of character.

...

Stranger: The moderate natures look for a partner like themselves, and so far as they can, they choose their wives from women of the quiet type. When they have daughters to bestow in marriage, once again they look for this type of character in the prospective husband. The courageous class does just the same thing and looks for others of the same type. All this goes on, though both types should be doing exactly the opposite.

Yes, he's arguing for exactly what we in the modern world call "eugenics," and which we know is a disaster in the hands of a government.

But does that mean that it's bad advice?

Consider that what Plato is saying here is "Marry someone whose strengths balance your weaknesses." The exact same idea is found in Carl Jung under the heading "Animus and Anima." And note that Plato very explicitly does not say something like "Men are aggressive and should therefore look for passive women to find balance," as one might expect from some of our modern "conservatives." No-- he says "Any person can be of the more active or more passive type, and both are necessary for a society. In a good marriage, an active woman is balanced by a passive man, or an active man by a passive woman." To my mind, that's exceedingly good advice-- to individuals. From a spiritual perspective, it can also be described as balancing fire and water or yin and yang energies.

As far as the Science of Kingship itself, this can be applied to any situation, from a political ruler to a church to a corporate boardroom. Anyone who has authority over any group of people, whether a nation or simply their own children, is a king, and can and should acquire and use the Science of Kingship.

Concluding: Who Is Above The Law?After all this, I have to tell you that the best way to come to understand Plato's political writings is simply to read them. The Republic, Statesman and Laws are fun to read and, if you practice it, great sources of themes for discursive meditation. While you read them, ask yourself: How can I apply these ideas to my own life? Not to the ancient world which no longer exists, much less to (God help us) reforming society according to some ideal image, but to becoming a True King over yourself above all, and in all those situations which call for the exercise of leadership, wisdom, justice, courage and self-mastery.

Let me give one example before we go.

The Laws is-- you may have guessed this-- an entire book of laws for a hypothetical colony. Early on in the dialogue, Plato tells us that the very best society doesn't need laws-- its people hold all things in common-- including wives-- and live together as one. Is he arguing for Communism? No-- Such a society cannot be found on this earth, but is suitable only for gods or demigods (Compare Jesus: "In Heaven there is no marrying or giving in marriage.) On this Earth the best we can do is to imitate the ideal, the heavenly society; and so the laws he gives are only the second-best form of society. And then he tells us, "But you're probably only going to end up with the third best." He promises to tell us what the third best form of society might look like... and then never gets around to it.

Meanwhile, in the Statesman, Plato also discusses the nature of law. Here, he says that the worst sorts of societies are lawless. Does that mean that societies governed by law are best? No, not at all. Law is only an imitation of the statesmanship of the True King. In real life-- as you know and as I know-- the actual situations we encounter and the people we encounter in them are far too variable to be covered under any code of laws, no matter how extensive. The True King does not rule by laws, but by Science: That is, a True Knowledge of what is good and evil. Rather than legal codes of the "Thou shalt not" variety, he governs by applying unchanging, eternal

principles, to everchanging, particular

situations.

Now, is it possible for our nations to be governed in this way?

Of course not. Plato is literally saying that the True King is above the law, and he means it. When our leaders set themselves above the law, they merely cast themselves below it.

At the political level, we must have laws and be governed by laws, and no one must be above them.

But what about the other levels? How do Plato's insights apply to those other inheritors of the fragments of the polis-- that is, the family, and the church?

Are we really to suppose, for example, that God Himself governs according to a mere petty legalist, checking our good and bad deeds and, above all, our opinions against a written set of rules that decide whether we get into Heaven or get tossed into the fire? Or do we suppose that he is a True King, applying eternal principles which He knows best of all to the everchanging situations of our material universe?

And, if we suppose that God is a True King-- as I believe He is-- how can we imitate him in our daily affairs, especially those under our own authority? Can we become better parents by rising above our own laws? Better managers? Better priests, teachers, ministers, spouses, friends?

I think so. What do you think?

Rushing to work today to make an 11:30 appointment, I looked down at my phone to make sure I had the time correct and discovered that the appointment had been canceled sometime between the time I left the house and that moment. And, looking at my phone, I managed to miss my exit, and drove some 20 more minutes into the mountains of Western Virginia before realizing what I had done. I now find myself sitting at a coffeeshop in a place called Purcellville, with several hours to kill, or to use.

Rushing to work today to make an 11:30 appointment, I looked down at my phone to make sure I had the time correct and discovered that the appointment had been canceled sometime between the time I left the house and that moment. And, looking at my phone, I managed to miss my exit, and drove some 20 more minutes into the mountains of Western Virginia before realizing what I had done. I now find myself sitting at a coffeeshop in a place called Purcellville, with several hours to kill, or to use.