Life Without Games, Part IV

Sep. 22nd, 2023 09:27 am

The Story So Far

Over the course of the last three posts, we've looked at the Transactional Analysis theory of Eric Berne, and the Dramatic Triangle of his student Stephen Karpman. I want to briefly summarize these ideas before we continue.

Transactional Analysis views social life as consisting largely of unconscious games, semi-conscious rituals and pastimes, and conscious (formal) rituals, and conscious procedures and operations. These are collectively known as transactions.

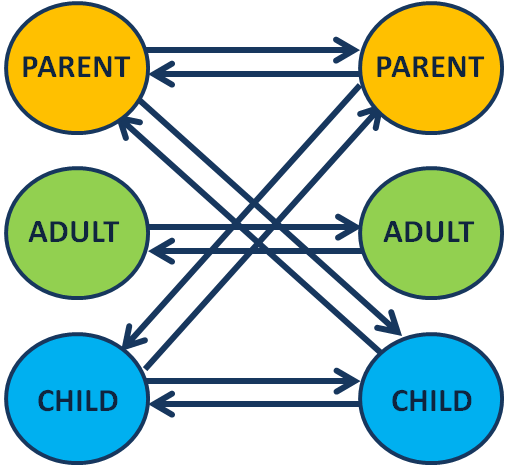

As individuals, we are capable of manifesting three different ego-states, which Berne calls the Parent, the Adult, and the Child. The Parent is concerned with judgment and opinion. The Parent may be overt or covert, and consists in behaviors learned from one's own parents. In the overt or direct Parental ego state, the individual simply behaves like one of his or her parents; in the covert or indirect state, he or she acts as their parent taught him or her to act. The Child is also dyadic. The Natural Child includes the individual's capacity for spontaneity, creativity, and wonder. The Adapted Child consists of behavior patterns learned in childhood, often in response to trauma. The Adult, meanwhile, is capable of reason, planning, and objective analysis.

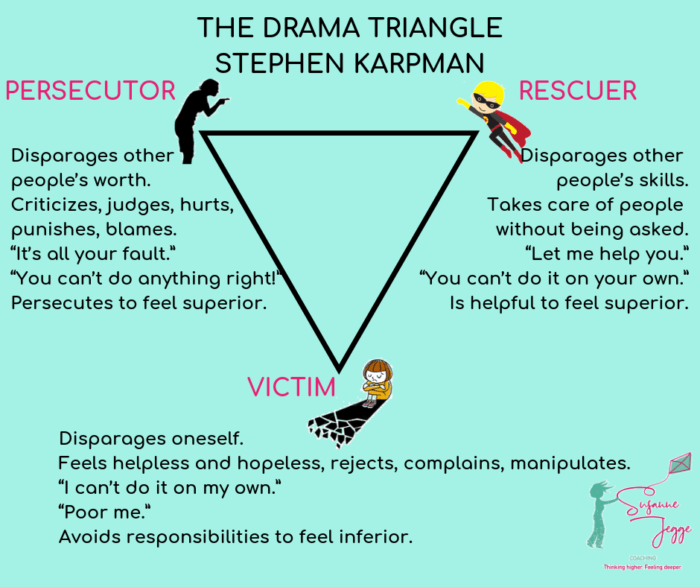

In the Karpman Drama Triangle, individual's take one of three roles, viz. the Hero or Rescuer, the Victim, and Villain or Persecutor. Very often, these roles are learned in childhood, and so may be considedred functions of the Adapted Child. Although the Rescuer sees himself as a hero, and the victim sees himself as innocent, none of these roles are actually innocent; all are pathological. Their continued interaction produces Drama and human suffering.

And so we have an image of our predicament. We are-- frequently or occasionally, as the case may be-- trapped in a series of programmed behaviors, not at all unlike NPCs in a videogame.

Now the question becomes, what are we to do about it?

The Shadows in the Cave

In The Return of the King, Frodo says the following to Sam regarding the monstrous Orcs:

In the previous series on this blog, I discussed the way that these concepts are understood in the tradition of the Druid Revival. This world of Shadows, Plato's Cave, is what we call Abred. In its lowest reaches it is Annwn, the world of the Dead. When we ourselves behave as automotons, we are essentially behaving as if we were ghosts. Thus Abred and Annwn are in a real sense identical to one another; most of our life here in Abred-- this place where we are supposedly alive-- is the life of a ghost. Riffing on the similarity between the Greek word "soma," which means body, and "Sema," which means "tomb," Plato wrote that "Soma is sema," the body is a tomb. I haven't seen a discussion of this anwyhere, but I've often wondered if his "cave" is not a natural cave, but a round barrow, an artificial burial chamber of a type that was employed throughout Europe during the Bronze Age. The goal of the spiritual life is to become aware of the true nature of this world and find our way out of the Cave, into the Sunlight of the Real World.

And so this is a world of the Dead, and it is also a world of Shadows. That is to say: The objects we encounter here with our senses are less than real. But, again, they aren't totally novel. The Shadow cannot create. Rather, they are reflections of a higher, truer, and more real plane of existence.

If all of this is true then two things follow:

First, all of these destructive patterns, including the games analyzed by Berne, the Karpman drama triangle, and the maladapted forms of the Child and Parent ego-state must be relfections, however dim, of higher, truer, and more noble ideals.

Second, the process of overcoming game-playing, roleplaying, and other automatic behaviors of these sorts is identical to the process of escape from Plato's Cave.

The Supernal Triad and the Dramatic Triangle

When we meet with a destructive automatism such as the Karpman drama triangle, our question should be, "Of what higher power or more noble ideal is this a base reflection?" After all, it could not have any existence-- even a shadow's existence-- if it weren't a reflection of something of the higher realms, and ultimately of something in the Divine. The Orcs are always corruptions, never creations.

The Hero and the Hero

Let's start with the Rescuer. Also called the Hero, and for good reason. Hero, in ancient philosophy, is a technical terms. The Heroes were a class of souls intermediate between angels or the higher daimones and ordinary human beings. Like every being, from the archangels on down through the ranks of daimones, to human beings, to animals, plants, and minerals, they exist as part of a chain of emanation from the highest gods. This is why in mythology and legend they are termed "sons of Gods." Romulus is a son of Mars, Aeneas is a son of Venus, and so on. Every being manifests the powers and activities of a particular god on their peculiar level of existence. In Classical times, Socrates, Plato and Pythagoras were venerated as heroes in the series of Apollo. In Christian terms, heroes are called saints; other traditions might call them xian or boddhisattvas. As in modern times, the Catholic and Orthodox churches have procedures for canonizing a person as a saint only after they have died, so in ancient times it was only after death that a man was discovered to have been a hero and to have been fathered by a God. Thus an ordinary soul may be seen to ascend to the rank of "Hero." In Christianity, the goal is for every person to become a saint.

We can say, then, that in the performance of the Rescuer role, an ordinary soul is trying to become a Hero. The trouble is that they are not doing it in the right way, or for the right reasons. The Rescuer rescues for the sake of his own ego, and so he is always looking for Victims, and for Persecutors. He claims his motive is Justice, but it is only a parody of Justice. This is because actual Justice consists in the right relationship between things, and, as we have seen, one cannot have a relationship with a Persecutor or a Victim. Relationships require truth. The Rescuer is always on the lookout for more Victims to save, and so he absolutely cannot allow his Victims to form their own identities or their own opinions. If you look at radical left-wing literature you will find an enormous amount of this sort of thing. Whenever any identified Victim-class-- proletarians, women, people of color-- refuses to accept the identity given to them by the Rescuer-activist, this can be ascribed to concepts like "false consciousness" or "societal Stockholme syndrome." This allows the Rescuer to keep rescuing a Victim no matter what the Victim herself wants.

And so the Antidote to the Rescuer is to develop a sense of Justice. Actual Justice is the right relationship between things, starting with the right relationship between the components of one's own soul. Before we try to help someone, we must ask ourselves if they need our help, if they have asked for it, if the sort of help they're asking for will actually do anything to improve their circumstances, and what we ourselves are getting out of it. If you lend her that six hundred dollars, will it really help her in the long run? When you listen to him rant for hours on the phone about how awful it all is and everything that They've done to him this time, will it improve his circumstances in any way? And if the answer is "No," as it usually is, the next question to ask is, "What are you getting out of it?"

And what about Victims, and Persecutors?

The Victim and the Wise Man

In the first case, it must be said that sometimes we actually are victims-- that is, real victims, rather than Victims with a capital v. Sometimes someone hurts you, and you didn't see it coming, and you didn't have the opportunity to get out of the way. Sometimes a natural disaster forcers you to leave home, or a global disaster forces you to stay in your house for months on end. Sometimes a war breaks out. Sometimes a large number of your political opponents declare that everyone who looks like you or who believes the things you believe is evil, and launches a society-wide campaign to harm you. It really does happen.

These are real situations. The trouble again is how we respond to them. We become Victims when we adopt that role as our identity. We become Victims when we stop trying to either help ourselves, or to learn from a difficult situation, or to maintain our self-control, but instead delight in our suffering, refuse everything that could help us, and make matters even worse than they were. The Victim, then, is a parody of the capacity to be affected by events, which is, also, ultimately, the capacity for wisdom. This may seen odd, but consider that there is no awareness of any kind without change; to become aware of any object of knowledge one must be affected by it, and therefore be changed by it. In this life some things are in our power, many other things are not. Wisdom consists, in part, in knowing the difference; it also consists in learning how to respond to situations, especially those which are largely beyond our control The best illustration of this principle, to my mind, comes from a well-known passage from the Discourses of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus:

The Villain and the Brave Man

Sometimes the ship is sinking, and there is nothing to be done.

But sometimes, the ship is not sinking, but is being sunk. And sometimes there is something that can be done.

Suppose the same two men on the same voyage. But now the ship is attacked, and pirates come on board. Imagine them swinging cutlasses, saying "Yarr," and all the rest of it. Suppose there are women and children on board, and these will surely be taken and sold into slavery if the pirates prevail. And suppose both of our men have swords.

Now, in one sense, we would seem to have a classic Dramatic Triangle. The pirates are the persecutors, the women and childrne, the Victims, the crew and our men with swords, potentially at least, the Heroes.

Suppose one of our men has spent the last year reading books by Eric Berne and Stephen Karpman. He's gotten in touch with his Inner Child, and he read today's blog post and so he knows that line form Epicetus. And so he throws down his sword and stretches out his neck to the pirates, saying, "It would be better to die now that my hour has come, then to play your game and become a Persecutor in my turn."

And the pirates cut off his head. The End.

Except that his friend is still alive, and he still has his sword. There is still something that can be done. But if he is going to do anything, he is going to need to call upon a reserve of violent, aggressive energy from somewhere within himself. This is a major part of the thymos as a component of the soul, and the reason that this word is often interpreted as "anger." It's why I usually translate thymos as heart. If he has the heart, he will unsheathe his sword, charge the pirates, and kick their lousy asses back into the ocean. And you had better believe that he is going to have to act like a Persecutor in order to do so.

And so the Persecutor role is revealed to be a shadow of Courage. Suppose our pirate-slayer, upon defeating his enemies, discovers that actually, he really enjoyed the fight with the pirates. He especially liked how scared they were when he charged them, and how good it felt to hurt them. And so after the voyage, he gets his own ship, and he goes looking for pirates. Before long, he's cleared all the pirates out of the Sea, probably hanging them publicly. But it's still not enough. There have to be other pirates out there. Or friends of pirates. Or people who know pirates, or who could be pirates if given the opportunity. Years go by, bodies hang from the gallows, and our brave man has become a Persecutor in his turn.

And so we see that the antidote to Rescuing is Justice of which Rescuing is a shadow. The antidote to Victimhood is Wisdom, of which victimhood is a shadow. And the antidote to Persecution is Courage, of which Persecution is a shadow.

These three together form the virtue of Temperance, which is self-control derived from self-knowledge.

On another level, the Persecutor is a shadow of the divine capacity of action; the Victim is a shadow of the capacity for affection; and the Rescuer is a shadow of the capacity for reflection. These three are also the supernal triad of Kether, Chokhma, and Binah. On a human level, these manifest as the virtues of patience, which is the capacity to suffer what must be endured; courage, which is the capacity to change what is amanable to change; and wisdom, which discerns between the two.

That, of course, will sound familiar, and it suggests a short spell as an antidote to the Rescue Game:

To Be Free Is To Be Alive

Of course, it isn't enough simply to know the words to a prayer or a quotation from Epictetus. To become free of these sorts of automatic behaviors is quite literally to become alive, after spending what seemed like life as ghosts in a ghost-world. This requires a great deal of ongoing work. And there is not one method, but there are many. In the next post I want to discuss some of those methods, and in so doing to together this series of posts and the previous one.