I know I promised to continue the discussion of Christian Platonism this time, but the Muse speaks as she will, and just now she's led me to write a long discussion of Druidry and Platonism, while the next post on Christianity is only half finished. So we're going to shift gears a bit, and return to Christianity next time. It may be worth mentioning that this is the longest post by far that I have ever written for this blog.

Platonic Druidry, Druid Platonism

I should start by saying that to say “Druid Platonism” is a bit redundant. The modern Druid Revival-- which is the sort of Druidry I’ll be discussing here-- was heavily influenced by Platonism from the beginning, and for a very good reason. No one really knows what exactly the ancient Druids believed in. All we have are a few fragmentary records, largely written down by their enemies, and some hints in the archaeological record. When the Druid Revival began in the 18th Century in Wales and England, its proponents were forced to look around for sources to fill in the patchwork of legends with which they’d been left.

A century prior, an influential group of Anglican theologians and philosophers at Cambridge had drawn on Plato and Platonism to combat the rising tides of materialism and Calvinism in English academic circles and the English Church. The work of the Cambridge Platonists is almost certainly part of the hidden backdrop of the Druid Revival, though I’ve never heard anyone discuss it directly. Meanwhile, contemporary with the Druid Revival, there was a more direct revival of Platonic philosophy in the work and the person of Thomas Taylor.

Taylor-- pour out a glass of beer to his Genius-- is the first author to have translated the works of Plato into English, as well as those of Aristotle, Proclus, Plotinus, Porphyry and Iamblichus. Taylor’s translations were read by William Blake, one of the founding fathers of the Romantic movement and-- critically-- one of the chiefs of the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids. They were also read by Ralph Waldo Emerson, G.R.S. Meade, and later by the founders of the Golden Dawn. Since then, even as his works have gone out of print, the fingerprints of Thomas Taylor are all over the alternative and nature-oriented spiritual traditions of Britain and North America.

But did I say alternative? Is it really so? Emerson is one of the founding fathers not only of American letters but of American culture. The movement that Blake inspired produced many of the greatest works of poetry in the English language. His influence, Taylor’s influence and, above all, the influence of Plato and the later philosophers in the Platonic tradition is all over American and English literature and art, and all of the best of it. Wordsworth and Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, Emerson, Tennyson, Yeats-- we have them all thanks to Plato and the late Platonists, and we have the Platonists thanks to Taylor.

Well, that was a big digression to make a small point-- Platonism has been part of contemporary Druidry since it’s beginnings, and so it doesn’t require any sort of radical change to draw upon it. What I want to do here, though, is to go into detail about some of the ways that we can use Platonic ideas to think about the concepts, practices, and gods of the Druid Revival.

Not Dogma

Before we proceed, I want to emphasize that nothing that follows should be taken as a statement of doctrine or “belief.” I’m not trying to present a set of opinions that you have to “believe in” to be a Druid, or to present the One True Druidry, or anything similar.

Moving right along. Let’s ask the question: If Druidry is already Platonic, why call it Druidry at all? Why not just call it “Platonism” or “Celtic Platonism” and be done with it?

A Difference of Emphasis

Inscribed over the entrance to the Academy at Athens were the words “Let No One Enter Here Who Does Not Know Geometry.” Following his predecessors, the Pythagoreans-- you didn’t think Plato came out of nowhere, did you?-- Plato used mathematics as a bridge between the sensible and the Intelligible worlds.

We discussed how this works in the first post in this series. There, I gave the example of the Pythagorean Theorem: Though the perfect Right Triangle it describes exists nowhere in sensible reality, it shapes and determines hte geometries of all the imperfect triangles of our material world.

Numbers themselves function in the same way. Consider one. No, not The One-- not yet, at any rate. Just stick with 1 itself, the first number you learned when you first started to count. (My daughter learned it when she was only one years old; “One” was one of her first words.) One is a number, but it is more than that: It is the basis for all number. How many numbers 2 are there? Just one. How many 3s? Just one. And so on. Thus 1 provides being and unity to every number which follows it; the One Itself is the same principle applied to all things.

In the world of Druidry, all of the foregoing holds good. Indeed, many Druids are very familiar with number symbolism, sacred geometry, and so on-- and I encourage those that don’t know these things to get to know them!

But the focus of Druidry is not the world of Number, but the world of Nature. Numbers and mathematical formulae are examples of Ideas, the Intellectual Powers that shape the succeeding worlds of Psyche and Matter.

There are other Ideas. If A:B::C:D, then A:C::B:D. This is an example of a logical formula. It can be applied to mathematics in the form 2:4::6:12 therefore 2:6::4:12. But it can also be applied to human society in a form like If the King is to the City as the Nous is to the Soul, then the King is to the Nous as the People are to the Soul. This analogy, in fact, is one of those that undergird Plato’s political writings.

And Ideas can also be found in the world of Nature.

The most fundamental tenet of a Platonic Druidry, then, is the encounter with the Ideas as they manifest in the world of Nature.

The Idea in Nature

What does this look like in practice? Well, one of the really fun things about Druidry is that, while its roots are ancient, it’s a young tradition. And the sciences that strongly relate to it-- that would be ecology and systems theory-- are also very young. So there is a lot of work still to be done-- and we get to do it all!

But here is an example, drawn from my time spent working in the wilderness in Oregon. There lands west of the Cascade Mountains are covered by temperate rainforests, and the dominant trees in these forests are huge conifers-- Douglas Firs, Grand Firs, Western Red Cedar and Western Hemlock. The trees grow to enormous size, and provide a home in their massive canopies for countless birds, mammals and insects. But they also block the sun completely, so that only a few shade tolerant understory plants (mainly salal, swordfern, and Oregon graperoot) grow in the understory.

And then they die.

Now, when the old trees die, they die standing up. For months, years, or longer, a tree will rot from the inside out, becoming a gigantic snag standing in the middle of the forest. Eventually it falls. Sometimes it falls in the wind, but in this case, let’s say it’s something more violent. Let’s zoom in on one single tree-- an ancient, majestic Douglas Fir, grown brittle and dry with age.

And watch, as a blast of lightning pours down from Heaven and strikes the tree. There is a terrible roar as the trunk of the great tree is shattered by the strike. It crashes to the Earth and instantly great walls of flame pour forth in every direction.

A moment ago, there was a mature and beautiful but static and unchanging old forest. Now there is heat, fire, and chaos, and death and terror for the creatures who live in this place. Birds fly in every direction, deer and elk scramble to keep ahead of the blaze. Tree after tree is consumed with flames like a gigantic bonfire.

And when you come back, a few days or a week later, where there once was a forest, there is now a smoking ruin of ash and soot and blackened branches.

Sounds terrible, doesn’t it?

Keep watching.

The first plants to make their appearance are weeds. In this part of hte world, that often means hardy blackberry and Scotch broom; government scientists call them “invasive” because they grew somewhere else before Europeans arrived here (from somewhere else) and spend enormous amounts of money to try to remove them, but fail. To the plants it doesn’t matter. The lightning and the fire have released enormous amounts of organic fertilizer that had been locked up the giant trees, and now they’re growing like your lawn would if you covered it in fertilizer and ignored it for a month.

The weeds provide food for insects, which themselves feed birds and mammals. The thicker clumps of weeds provide homes for rodents, racoons, foxes and feral cats (some of these are government approved; others are not.) Shrubs appear, and provide nesting places for birds.

Year by year, the weeds die, and their bodies, mixed with the manure provided by the animals, becomes part of the soil, which is also enriched by the wood char lying everywhere. The soil thickens, and taller shrubs and small trees begin to grow. Ash and alder in low lying areas, oaks on open grounds and slopes. Where the fir trees had grown as nearly a monoculture, now many different types of plants and animals thrive here.

Over time, the landscape will stabilize into an oak woodland, with clusters of oak trees broken up by open areas, grazed by elk and black tail deer. Predators which are capable of hunting these will follow in due course.

And eventually, the oaks themselves will give way to the seedlings of fir trees and other conifers. They will grow tall, overshadow the oak, and, after a long time, the old forest will be restored. And the conifers will grow old, dry up, and die, and then with a new blast of fire from the heavens the cycle will start again.

The terms change, but the relations remain constant.

Imagine the forest. It grows old and brittle and unchanging. Fire comes and chaos and pain-- but out of chaos, new life. See this as a pattern, just like the Pythagorean Theorem or the logical formula given above. Have you ever seen it manifested in your own life? I know I have. What about the life of a people or a nation, or an entire civilization?

The One

As we’ve discussed, the First Term in Platonism is the One; it is from the One that everything which exists has its being. The One is also called the Good, because the highest term is identical to Goodness Itself.

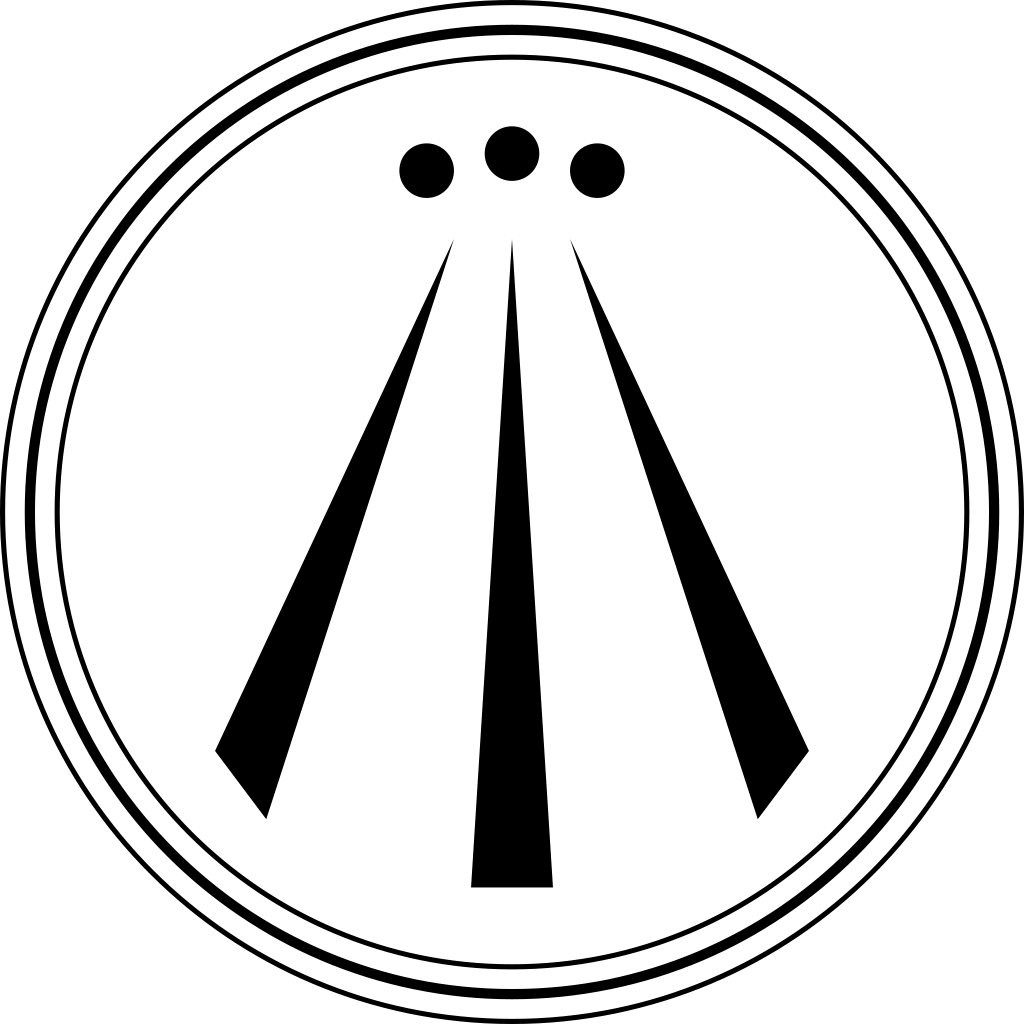

In Druidry, we have an equivalent to the One in the term Awen, and the idea of the Three Rays of Light.

Awen is a Welsh word meaning “muse” or “inspiration;” a poet can be called “awenydd,” “one who has Awen.” In contemporary Druidic thought, Awen is the highest principle; we can thus understand it as another name for the One. Indeed, it is helpful to see that this highest term can be given different names in different traditions. In the Chinese philosophical tradition, “Tao” expresses the same idea. Neither One, nor Tao, nor Awen entirely characterizes the First Principle, as this is impossible for the human mind. Rather, each name we give to it allows us to understand it in a different way. In the poetic mode of thought common to all the Celtic peoples, Awen or inspiration is a perfect name for it. It teaches us to see, in the beauty of works of art and literature, something akin to the same power that produces the entire cosmos, that expresses itself in Nature, and that is also to be seen any time a human being lives according to his or her full potential.

Although we each have our own Awen, at the beginning of our lives it isn’t very clear; our souls are muddled and their parts disconnected, and we are weighed down with countless accretions from our culture or our personal karma, or elsewhere. The work of discovering and living one’s Awen is the work of encountering one’s true being and true purpose, and uniting ourselves to it. In just the same way, the task of the philosopher in the Platonic tradition is the gradual withdrawal from the world of sensibles, opinions and created things, to union with the Divine.

The Three Rays of Light

Awen is symbolized by the image of Three Rays of Light. These are named Gwron, Plenydd, and Alawn in Welsh, and their names are said to signify Knowledge, Power, and Peace. These three express the same idea as the Intelligible Triad that we discussed last time. Peace, Alawn, is Being Itself, the still and absolute center. Power, Plenydd, is Life, the activity of being. Knowledge, Gwron, is Nous, the awareness of being. These three together are Awen, which is also known by the name OIW, the highest expression of the Divine which can be understood by the human mind.

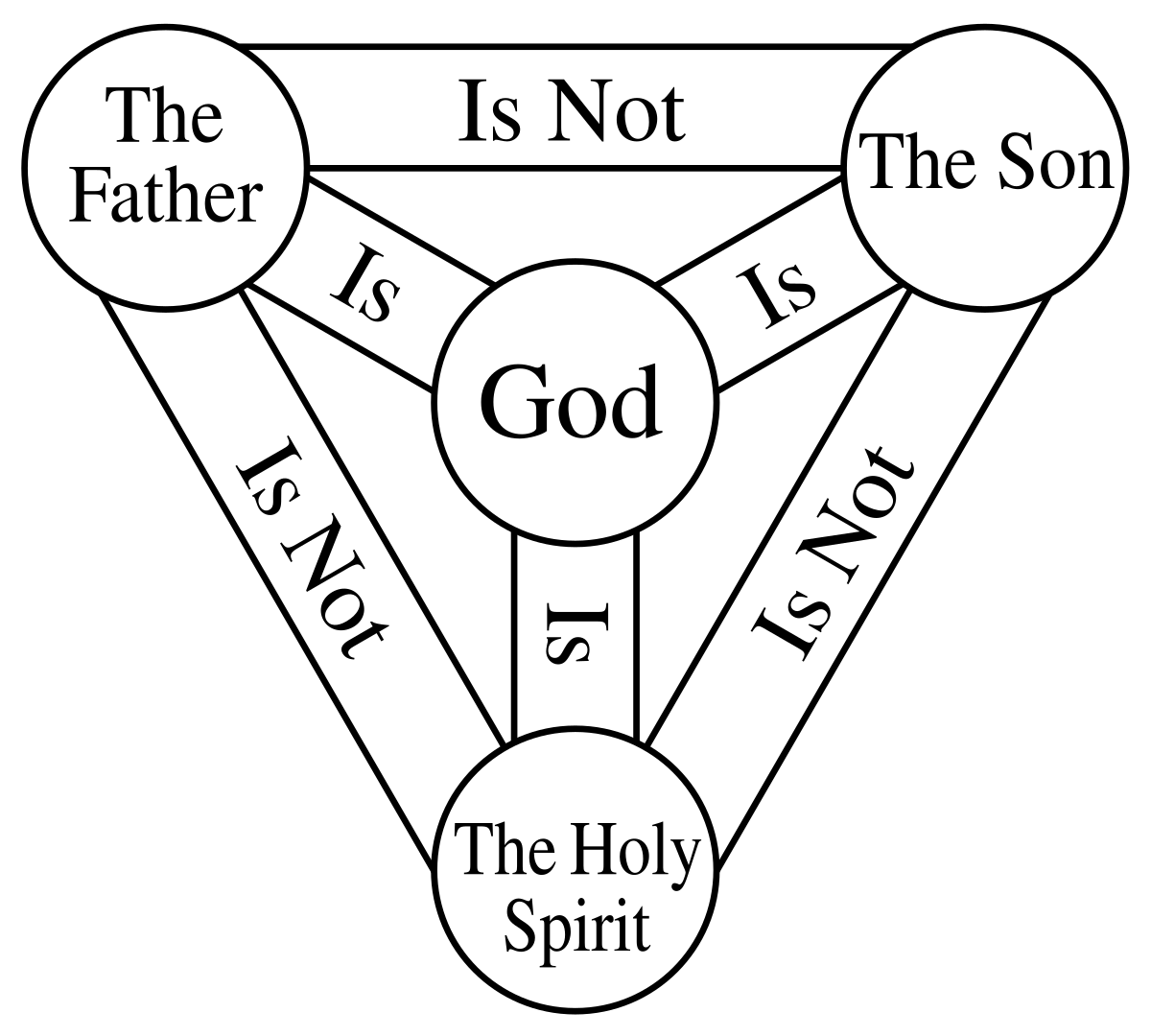

The third term in every Platonic Triad has two powers: It both returns to the first, and also recapitulates the first at a lower level. Thus from the third term in one triad, succeeding triads arise. From these triads are the unfolding of all the many Gods which bring the world of experience into being.

Succeeding Triads

Imagine the relationship of the Sun to the Earth. First there is the Sun, abiding in itself. Next, there is the light that shines forth from the Sun. Third, the light is received by the Earth. Now the process of creation begins, as the light is received by the Earth and turned into energy for living beings and the bodies of plants. From the interaction of Light and Earth, life emerges.

In Druidic terms, the Sun Itself is the OIW. The light which emerges is Hu the Mighty, the Great Druid God who drives forth darkness. The Earth is Ced the Earth Mother, who brings forth all living things.

These Three are another articulation of the Intelligible Triad. They also reveal another Platonic Triad, that of abiding, processing, and reversing. The Sun abides; the light goes forth; receiving the light, the Earth reflects it back to the Sun. If you were able to stand on the surface of the Sun, you could see the Earth, and what you were seeing would be the Sun’s light reflected back to you. In just the same way, our souls descend from the Eternal Unity of Spirit into material incarnation, and rise back up again to Spirit. (Is there a part of our soul which abides eternally, as the Sun stays where it is and shines its life forth? That’s a fine debate; Plotinus thought so, Iamblichus disagreed. What do you think?)

Here is another Triad, drawn from Plato’s Timaeus.

First there is the Form. The form is received by something which is at once form-like and yet altogether formless and without quality. The Formless provides the substance to the Form, and from these the Formed emerges. This triad of the Form, the Formless, and the Formed can also be called Father (Form), Mother (Formless), and Son (Formed). In Druidry, these are the Triad of Hu, the light; Ced, the substance, and their progeny, Hesus, Chief of Tree Spirits.

Hesus is an interesting figure. His name is a variation on the old Gaulish deity Esus, with the H added to emphasize the presence within his being of the power of Hu the Mighty, his progenitor. In the Druid traditions that I follow, he is the Power that dwells in the heart of the Sacred Oak, the guide of Druids, patron of healers, and teacher of wisdom. As the master of the trees, Hesus is the master of all forests and all plant-life. As the master of plant life, he is the master of the basis of Life Itself, as this is made possible only by the plants which absorb the light of the Sun and form it into food for succeeding orders of creatures. As we approach the forest, we can turn our minds toward Hesus and ask him to guide us to wisdom.

Ones and the One

Little is known of the ancient Celts and their religious practices, as I said above. We do know one very interesting thing about their religion, and that is their method of naming the Gods. Many divine names, it seems, were not so much names as titles. “Cernunnos,” for example, is one old Celtic God; his name means “he of the horns.” And, appropriately, Cernunnos was a Horned God. “Belenos” was another god; his name appears to have meant “the shining one” or the bright one”; in Roman Gaul he was seen as a form of Apollo. “Epona” is a goddess; her name means “she of the horses.”

And so here we have the convention: the suffix “unos” is added to a quality to give the name of a God; the suffix “ona” is added to give the name of a goddess. “Unos” and “ona,” meanwhile, are derived from the word for One.

In the thought of the late Platonic philosopher Proclus, the Gods are those beings which have their being in the One Itself. They can also be called “henads,” which means “unities;” the Gods particularize the One, bringing forth succeeding series of beings. A Goddess of Horses is absolute divinity manifesting as the power which brings into being horses and everything which relates to them. “Epona,” then, is a perfect name for this being “The One of the Horses.”

One of the issues that modern Druids who want a more polytheistic approach to their spirituality face is the paucity of available deities. Anyone who wants to work with the gods of Greece and Rome has an abundance of sources, the names and stories of hundreds of gods, spirits, and heroes. But those looking for a more Celtic “flavor” to their spiritual life are in a bind.

Knowledge of the old naming formula allows us to overcome this issue. Assume all the following to be true:

1. Awen is also called the One, and is the power which underlies all being.

2. Gods are beings which are most closely united to the One.

3. Everything in the world of our experience has its source in a God.

4. It’s much easier for a human mind to interact with a God if we have a name and a gender to assign to it.

We can use the old Celtic naming convention to designate Gods, which can then become the objects of prayer and contemplation.

How does this work? It’s simple. If you want to interact with a deity, and don’t have a name for it, look up the word for whatever it governs in Welsh or another Brythonic Celtic language. Then tack on “Unos” or “Ona.” Which one? That’s sort of up to you. The gods are designated masculine or feminine to show that, in addition to having unity, they have the power to generate: Generation is accomplished through gender. Masculinity can be defined as the sort of creativity which generates new forms by going outside of itself and mingling with other things. Femininity is the sort of creativity which generates new forms by drawing things into itself and mingling them with its own substance and power. If you’re want to bless your garden, and if gardens seem feminine to you, you might pray to “Garddona”-- that’s the Welsh word “gardd” for garden, with “ona” added on. If you’re out walking through the woods on a winter’s day and you find yourself moved by the beauty of the snow falling, you might give thanks to “Gwyntonos,” the “one of the snow.”

Now, it needs to be said that the words that will result from this process will almost always be complete nonsense. That’s okay. In fact, it’s important. By being unintelligible, the foreign word allows us to rise above the thinking mind. That’s also a reason to use words in a language you yourself don’t know, by the way-- saying “The One of the Snows” in English could work, but it doesn’t have the same power to kick your thinking above the level of dianoia. In magic, these sorts of half-comprehensible names for gods and spirits are called “the barbarous names of evocation,” and the old books include severe injunctions never to change them.

Since there are still people who speak the modern Welsh tongue-- and since getting offended about other people using languages is a popular past-time these days-- it would be even better to use an extinct language. A dictionary of Old Gaulish would be particularly useful, as there are no old Gauls around either to understand what you’re saying or get offended about your saying it. But, of course, you can always decide that you don’t care those sorts of things, and use whatever words you can come up with on Google Translate.

Beauty

Beauty is one of the most important parts of Platonic philosophy, and one about which we haven’t much to say. But Platonic philosophy isn’t all reading and math homework. Plato had a sense of humor, and also a sense of raunchiness, though both of these are often lost in the later commentators. Beauty and erotic love are central concerns for Plato.

Now Beauty, in this tradition, is not any kind of mere prettiness, and it isn’t a matter of “taste” or “in the eye of the beholder.” Beauty in an object is the living presence of Beauty Itself, which is the presence of the Divine. Oh, and Beauty isn’t just physical beauty. This is something that is often very hard for modern people to understand, but in the Platonic tradition, “beauty” can be found both in physical objects, like a beautiful forest or a beautiful face, and in beautiful actions. Beautiful actions, of course, are those which arise from the virtues.

Nor is the practice of Platonic philosophy all reading and thinking about stuff. Techniques both of contemplative meditation and ritual magic (theurgy) were taught in the Platonic schools. Different branches of the tradition emphasized one or the other-- Plotinus emphasized meditation, Iamblichus theurgy, and so on. But both are important. Just now, though, I’d like to talk about a particular technique of meditation which focuses on the contemplation of Beauty. This practice allows us to approach a particular object of beauty and to raise our consciousness by progressive degrees to the Divine.

Plato tells us how this works in the Symposium, a dialog which is especially concerned with the nature of Love, or Eros. In the dialog, Socrates relates how he was initiated into the nature of love by his teacher, a priestess named Diotima. Diotima teaches Socrates to move from the contemplation of a single beautiful image-- or person-- to beauty itself. “Starting with individual beauties, the quest for the universal beauty must find him ever mounting the heavenly ladder, stepping from rung to rung-- that is, from one to two, and from two to every lovely body, form bodily beauty to the beauty of institutions and laws, from institutions to learning, and from learning in general to the special lore that pertains to nothing but the beautiful itself-- until at last he comes to know what beauty is.”

Whoever has been initiated so far in the mysteries of Love and has viewed all these aspects of the beautiful in due succession, is at last drawing near the final revelation. ANd now, Socrates, there bursts upon him that wondrous vision which is the very soul of the beauty he has toiled so long for. It is an everlasting loveliness which neither comes nor goes, which neither flowers nor fades, for such beauty is the same on every hand, the same then as now, here as there, this way as that way, the same to every worshiper as it is to every other.

Nor will his vision of the beautiful take the form of a face, or of hands, or of anything that is of the flesh. It will be neither words, nor knowledge, nor a something that exists in something else, such as a living creature, or the Earth, or the Heavens, or anything that is-- but subsisting of itself and by itself in an Eternal Oneness, while every lovely thing partakes of it in such sort that, however much the parts may wax and wane, it will be neither more nor less, but still the same inviolable whole.

In the Symposium, Plato is talking about erotic love, and so the contemplation he discusses begins with the beauty of another person. Contemplating that person, the lover then considers what makes them beautiful, and then contemplates how that same beauty is manifest in others. In this way, he comes to realize how that beauty goes beyond any one individual. He then proceeds to contemplate what qualities that produce the sort of physical beauty he is contemplating are also manifest in human society at its best, in laws and the institutions of culture, in just actions and virtuous behavior. At this point, he attempts to realize a unified principle which underlies the beauty in question. Finally, he progresses, if he can, from a particular unifying principle, to unity itself, by seeing how the particular principle of beauty he has discovered is found in every form of beauty, and participates in what Diotima calls “the open sea of beauty.”

All this is very abstract, and we would do better to explain it by example. But now, as befits our purpose, let’s turn to the special emphasis of the Druid tradition: The Natural World.

A Druid Meditation on Natural Beauty

This practice takes the contemplation of beauty described in the Symposium and applies it to that most Druidly of actions: Taking a walk in the woods.

Step 1. Before you begin, either before you step out your door or before you step onto the path into the woods, say a prayer such as the following:

Oh Hesus, Chief of Tree Spirits, guide of Druids and teacher of wisdom, I pray that, as I venture into the Green World which is your kingdom, you will guide my soul to such wisdom as it is able to attain.

I like to then make a small offering at the beginning of any forest path before I enter. This can be as simple as pouring out a bit of water from your bottle. I say something like “In the name of Hesus, Chief of Tree Spirits, I pour out this water in offering to the spirits of this place. As you receive this offering, may I receive your wisdom.”

Step 2. Just walk. As you do, try to clear your mind of any stray thoughts, and focus your attention on the world around you. Keep an eye out for birds and animals, smell the air, touch the trees and the ground.

Step 3. Eventually, you will come across something particularly beautiful, on which you want to focus your attention and which you want to make the subject of your meditation. It may be the entire scene, or it may be some detail of it, like orange leaves in late Autumn or the scent of blackberries on the air in Summer, or it may be some particular object, like a bird’s nest in an ancient oak tree or a sunlight rippling on the surface of a stream.

Step 4. Focus your attention on the object of your contemplation. Experience it, enter into it, let yourself be totally enraptured with the beauty of it. Do this for as long as you like. You don’t have to be in any particular posture, by the way-- if it’s a static object, like a tree, you can stand or sit in a suitable meditation pose, but if it’s a larger scene, you can continue walking, slowly and reverently. Just make sure your body is poised but comfortable enough to not get in your way, and focus your attention on the object, filling your entire awareness in this way.

Ask yourself, what is it that makes this object beautiful?

If you’re focusing on a bird’s nest in a tree, it may be that you found yourself moved by the way that something as ancient as a centuries-old tree provides a home for the newborn life of the baby birds. It may be the interplay of solidity, represented by the tree, and fluidity, represented by the nest and its inhabitants; or it may be the interplay of the straight lines of hte branches with the circular lines of the nest. Any answer is correct.

Step 5. Consider where else in the natural world the same sort of beauty can be found. It might be that, in the same way that an ancient tree provides shelter for birds, a different and far more fleeting form of life, a tidal pool provides a home for molluscs and crustaceans, and your own gut is home to countless micro-organisms which aid you in the work of digestion. Or it could be that the interplay of solidity and stability seen in the birds and their tree can also be seen in a stream making its way through a stone channel or in fish spanning underneath a fallen log in a pool. Or it could be that the same relationship of straight and circular is also found in a lake overflowing into a stream or winds gathering into a vortex.

Step 6. From this contemplation, see if you can derive a general principle. “The ancient, abiding life which creates the home for the new and transient life.” “The creative power of the union of stability and change.” “The spiral as union of the circular and the straight.”

Step 7. Move in your mind from the realm of nature to the realm of human society and culture. Where can the same principles be found in humanity at its best? Perhaps the same care of the ancient and abiding for the young, different and fleeting can be seen in the way that the best constitutions are framed with the care of many generations in mind, far past those the framers themselves will ever see. And this same principle can be seen in wise parents that lay up savings for their children, their grandchildren, and beyond-- or in family stories and traditions, passed down from generation to generation. The interplay of stability and change can be seen in this way also, as laws that permit change but limit its pace and its direction, and the same laws as household rules laid down by parents for their children. The union of line and circle can be seen in a well-designed farmer’s market, which leads you on a straight path to circle through the stalls of the many vendors, or in the best forms of cultural practice, which allow periods of movement and change to alternate with periods of circling back toward old ways.

Step 8. Consider the foregoing, and add in a contemplation of how you can best make use of the same principle in your individual life. Maybe you could do some work toward making your own lawn or garden more like the tree, providing a stable home for those fleeting forms of life, butterflies and pollinators. Or maybe you could do a better job of providing a stable example for the young and changeable people you know. Or maybe it’s time to circle back to something you once knew and did well-- or to move forward in a line toward the next circle.

Step 9. Let us suppose that all of the ideas which you have experienced so far emanate from a single principle. We can give it a name, and here we can draw on the Celtic Naming Conventions given previously. “Hengoedenona” would mean something like “The One of the Old Tree” or, more poeticly, the Old Lady of the Trees. Solethylifunos is a combination of the words that (according to Google Translate) mean “Solid” and “Fluid” with the -unos suffix; it could be said to mean “The One Who Moves and Abides.” “Cylchalinnelona” is the Lady of Line and Circle.

Address yourself to this power and thank it, in your own words, for its wisdom. Try to reach out with your mind, letting go of all the details and particularities previously encountered, and stand only in the presence of this power, which is a God. Ask that you may manifest its light and its wisdom in your own life and bring its blessings with you back to the world of experience. If you want, you can create an image of the God in your mind; whatever seems appropriate, let it be filled and overflowing with light. As you speak to it, slowly allow everything but the Light to melt away, and imagine that Light spilling over from the ineffable One, through teh God that bears it, to you and to the entire world.

Step 10. Close with a suitable prayer. The Gorsedd or Universal Druid’s Prayer may be particularly appropriate:

Grant, oh God (Goddess, Gods, etc),

Thy Protection,

And in Protection, Strength,

And in Strength, Understanding,

And in Understanding, Knowledge,

And in Knowledge, the Knowledge of Justice,

And in the Knowledge of Justice, the Love of it,

And in the Love of Justice, the Love of All Existences,

And in the Love of All Existences, love of hte Gods, and the Earth, and all Goodness.

AWEN.

You may find it helpful, when you return to your home or your car or wherever you started, to write down any insights that came to you during this practice.

Rushing to work today to make an 11:30 appointment, I looked down at my phone to make sure I had the time correct and discovered that the appointment had been canceled sometime between the time I left the house and that moment. And, looking at my phone, I managed to miss my exit, and drove some 20 more minutes into the mountains of Western Virginia before realizing what I had done. I now find myself sitting at a coffeeshop in a place called Purcellville, with several hours to kill, or to use.

Rushing to work today to make an 11:30 appointment, I looked down at my phone to make sure I had the time correct and discovered that the appointment had been canceled sometime between the time I left the house and that moment. And, looking at my phone, I managed to miss my exit, and drove some 20 more minutes into the mountains of Western Virginia before realizing what I had done. I now find myself sitting at a coffeeshop in a place called Purcellville, with several hours to kill, or to use.