The Metaphysics of Reincarnation, Part 7

Jan. 3rd, 2024 12:39 pm

Today's post is necessarily going to be an overly short and, frankly, unfair treatment of a topic which needs larger consideration. At some point I may return to it, so consider this post a placeholder.

When you mention the word "reincarnation" to Americans, you'll very often find that the religion or philosophy that they associate it with is not Platonism, Gnosticism or even Hinduism, but Buddhism. Now, whether or not they are correct in this association is another matter, which we'll turn to presently. But for now it is enough to say that no discussion of the metaphysics of reincarnation would be complete without at least a cursory overview of the Buddhist tradition, which presents alternatives both to the Platonist-Gnostic and Aristotelean notions we've looked at so far.

Every word of the preceding paragraph is true, but to step forward from this point is to immediatley court controversy. There are at least three reasons for this. The first is simply that Buddhism itself is older than Christianity by some five centuries, and as such has had that much more time to spread and diversify. It has, moreover, from a far earlier date lacked an organizaton which could enforce an orthodox set of opinions. Rather than "Buddhism," there are many "Buddhisms," which at times differ greatly from one another. The second is that within the individual Buddhist traditions, there are differences of opinion on precisely this topic. One can find Japanese, Chinese, and Indian Buddhists arguing for or against various interpretations of reincarnation.

The third reason is simply that, here in the West, Buddhism has for a long time been marketed as a kind of up-market "rational religion" for atheists. This has resulted in a particular view of Buddhist teaching becoming widespread here.

Reincarnation or Rebirth?

The upshot of all of this is that there are many contemporary Buddhists-- especially in the West and especially online-- who object to the term reincarnation, and in fact insist that the Buddha never taught reincarnation, and that reincarnation doesn't exist. Now, so far, this is nothing terribly unfamiliar. Mainstream Christians, Muslims, and scientific-atheists insist on the same things. But there are two really odd things about this claim. The first is simply that the historical Buddha clearly taught reincarnation, and many, perhaps most, Buddhist scriptures accept reincarnation as a matter of fact. The second and even odder oddity is that the same teachers who claim that reincarnation does not happen are also willing to admit the existence of past life memories.

So what's going on here?

Six Realms of Rebirth

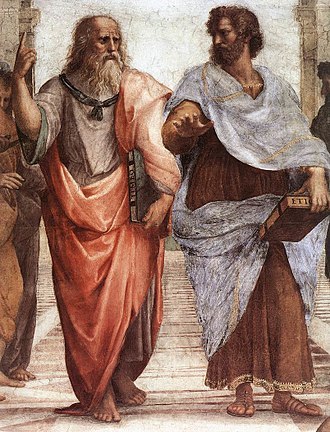

Reincarnation is central to the teachings of the historical Buddha, as the idea of reincarnation was widely known and taught in his time. It's well worth noting that, while the exact dates of the Buddha's lifetime are not known for certain, he was a contemporary either of Pythagoras of or Empedocles, both of whom, as we have seen, taught reincarnation. Now, the claim here is not that Buddha learned about reincarnation from Pythagoras or vice versa. In fact, both teachers claimed to have learned about reincarnation directly: that is to say, through their own memories. ( There is a discussion of reincarnation beliefs in early Buddhism here.)

Like many other teachers on this subject, the Buddha's view of reincarnation was not exactly a positive one. The Buddhist term samsara refers to the condition of constantly returning to incarnation, and this is seen as a condition of suffering from which we must escape. In this sense, the Buddhist take on reincarnation may be seen as another spin on the idea found both in Plato's teachings and in Gnosticism.

As in the case of Platonism, Buddhism traditionally teaches that there are many possible forms in which one may be reborn. Many Buddhist schools organize these into the Six Realms of Rebirth, representing six possible levels of existence. These are, in order from the most to the least pleasant:

1. Gods

2. Asuras (angelic beings below Gods but above mortals)

3. Human beings

4. Animals

5. Hungry Ghosts

6. Demons

After death, the mind enters into a liminal space, called Bardo in the Tibetan tradition, after which it takes rebirth in one of these six realms. Attentive readers will already note the similarities to Plato's Phaedo. The difference seems to be that Plato conflates the time spent in between incarnations with rebirth in one of the more pleasant parts of the spiritual world.

After death, the mind enters into a liminal space, called Bardo in the Tibetan tradition, after which it takes rebirth in one of these six realms. Attentive readers will already note the similarities to Plato's Phaedo. The difference seems to be that Plato conflates the time spent in between incarnations with rebirth in one of the more pleasant parts of the spiritual world.

Now, in the Platonic tradition, as we have seen, the souls of the just abide in a pleasant or heavenly part of the spiritual world-- but this is not the ultimate goal. The goal, rather, is, through the practice of Philosophy, to ascend beyond the cycle of death and rebirth. In the Buddhist tradition too this is the goal. There are two critical differences, however. First, Buddhism has a far more skeptical view of the realms of the Gods and Asuras than does Platonism. Some Buddhist traditions teach that one ascends to these realms through pride, not through virtue. Even those with a more positive view of the Divine realm see it as just another part of the cycle of Samsara, and thus a fate to be avoided. Second, the ultimate goal for the Platonists is ascent to the realm of the Ideas, or perhaps to the One Itself, depending upon who one is talking to. For the Buddhist, by contrast, the goal is Nirvana, which...

...Well, here again we run into difficulties. Sometimes, Nirvana is seen as a positive state of transcendent consciousness, in which one is no longer bound to fixed realities or conditioned states of existence. At other times, it is seen as a total cessation of all consciousness. And very often, it is both of these at once.

The result is that some forms of Buddhism are very similar to Platonism-- or, rather, can be seen as part of a family of traditions which includes Platonism and Gnosticism. The relationship between these traditions can be views in the following way:

Platonism, Gnosticism, Buddhism

The result is that some forms of Buddhism are very similar to Platonism-- or, rather, can be seen as part of a family of traditions which includes Platonism and Gnosticism. The relationship between these traditions can be views in the following way:

Platonism, Gnosticism, Buddhism

1. Platonism. The material world is a kind of prison, but its creator is a good Demiurge. After death, the human being abides in Tartarus, Hades, or Heaven for a time, experiencing either joy or suffering depending upon merit. Rebirth may be in human or animal form. The goal of the spiritual life is to transcend the cycle of reincarnation through the practice of Philosophy. The cycle of reincarnation may or may not begin anew for human souls during the next cycle of Creation.

2. Gnosticism. The material world is a prison, and its creator is an evil Demiurge. After death, the human being is recycled back into the prison house of matter, which is as good as being tossed into Hell. The goal of the spiritual life is to transcend the cycle of reincarnation through the achievement of Gnosis. The way of Gnosis was brought to mankind especially by Jesus, who was sent from the Divine Realm of the True God, who is above the Demiurge.

3. Buddhism. The material world is an illusion, and has no creator. The spiritual worlds are also illusions with no creators. Gods, angelic beings, humans, animals, spirits and devils are all trapped in the cycle of rebirth. The goal of the spiritual life is to transcend the cycle of reincarnation through Awakening. Awakening is achieved by following the Eight-Fold Path taught by Gautama Buddha.

American Buddhism

The foregoing should suffice for a very general comparison of Buddhism with other reincarnationist traditions. It remains to discuss the outlier, non-reincarnationist forms of Buddhism. And the reason to discuss this is simply that you're very likely to encounter it if you talk to modern Buddhists, especially in America and especially on the Internet.

The approach this type of Buddhism, which we might as well just call American Buddhism, takes to reincarnation can be seen in a video on the topic from a British Zen organization called Zenways. Note the claims that the teacher makes:

1. Past life memories occur to some people who meditate regularly (he estimates between 1 in 10 and 1 in 20 meditators will encounter this).

2. But the person in the past life isn't you.

3. On the other hand, the person in your own childhood memories isn't you either.

4. (Left unstated: But the childhood memories are somehow more you than the pastlife memories.)

The crux of this approach is point number 3, which is an expression of the idea of anatta. Anatta is a Buddhist doctrine meaning "no self." Its meaning in practice is that hte fixed self that you experience does not exist. Anatta is paired with another idea, "anitta," which means "impermanence." This refers to the way that all things move and change. In other words: There is no fixed self, and there is also no fixed world out there for the self to experience! Buddhist traditions which emphasize anitta and anatta tend to teach their followers to spend a great deal of time meditating on impermanence. Vipassana practitioners, for example, will spend hours, or even days, scanning their own bodies from crown to feet and back again, in order to notice how the body sensations exist in a state of continual flux. Enlighteningment, in this case, means the realization of the nonexistence of, basically, everything. In such a state, past-life memories happen, and present life memories happen, because there is some sort of connection between past and present-- but it's nothing to make a very great fuss about, because there is nothing really there at all.

If I'm being honest, I find it very hard to be polite about this tradition. At best I believe it's a great illustration of the classical Occult teaching: What you contemplate, you imitate. The flux that these Buddhists describe is what Platonism refers to as Chaos or the Indefinite Dyad, and it's identical with what I've identified as Cythraul or the Devil in the posts on Druidry. Contemplate Chaos, and you become Chaos. Contemplate nothing, you become nothing. This seems to have an enormous appeal especially to the upper class of America and Western Europe, for reasons that seem obvious enough.

2. Gnosticism. The material world is a prison, and its creator is an evil Demiurge. After death, the human being is recycled back into the prison house of matter, which is as good as being tossed into Hell. The goal of the spiritual life is to transcend the cycle of reincarnation through the achievement of Gnosis. The way of Gnosis was brought to mankind especially by Jesus, who was sent from the Divine Realm of the True God, who is above the Demiurge.

3. Buddhism. The material world is an illusion, and has no creator. The spiritual worlds are also illusions with no creators. Gods, angelic beings, humans, animals, spirits and devils are all trapped in the cycle of rebirth. The goal of the spiritual life is to transcend the cycle of reincarnation through Awakening. Awakening is achieved by following the Eight-Fold Path taught by Gautama Buddha.

American Buddhism

The foregoing should suffice for a very general comparison of Buddhism with other reincarnationist traditions. It remains to discuss the outlier, non-reincarnationist forms of Buddhism. And the reason to discuss this is simply that you're very likely to encounter it if you talk to modern Buddhists, especially in America and especially on the Internet.

The approach this type of Buddhism, which we might as well just call American Buddhism, takes to reincarnation can be seen in a video on the topic from a British Zen organization called Zenways. Note the claims that the teacher makes:

1. Past life memories occur to some people who meditate regularly (he estimates between 1 in 10 and 1 in 20 meditators will encounter this).

2. But the person in the past life isn't you.

3. On the other hand, the person in your own childhood memories isn't you either.

4. (Left unstated: But the childhood memories are somehow more you than the pastlife memories.)

The crux of this approach is point number 3, which is an expression of the idea of anatta. Anatta is a Buddhist doctrine meaning "no self." Its meaning in practice is that hte fixed self that you experience does not exist. Anatta is paired with another idea, "anitta," which means "impermanence." This refers to the way that all things move and change. In other words: There is no fixed self, and there is also no fixed world out there for the self to experience! Buddhist traditions which emphasize anitta and anatta tend to teach their followers to spend a great deal of time meditating on impermanence. Vipassana practitioners, for example, will spend hours, or even days, scanning their own bodies from crown to feet and back again, in order to notice how the body sensations exist in a state of continual flux. Enlighteningment, in this case, means the realization of the nonexistence of, basically, everything. In such a state, past-life memories happen, and present life memories happen, because there is some sort of connection between past and present-- but it's nothing to make a very great fuss about, because there is nothing really there at all.

If I'm being honest, I find it very hard to be polite about this tradition. At best I believe it's a great illustration of the classical Occult teaching: What you contemplate, you imitate. The flux that these Buddhists describe is what Platonism refers to as Chaos or the Indefinite Dyad, and it's identical with what I've identified as Cythraul or the Devil in the posts on Druidry. Contemplate Chaos, and you become Chaos. Contemplate nothing, you become nothing. This seems to have an enormous appeal especially to the upper class of America and Western Europe, for reasons that seem obvious enough.