The Metaphysics of Reincarnation, Part 5

Nov. 30th, 2023 09:36 am

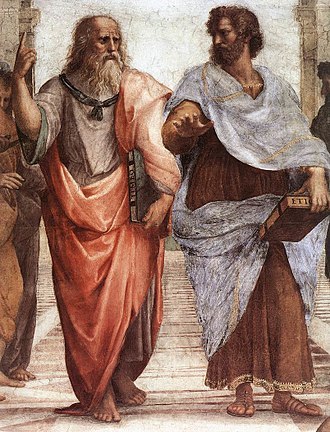

Everyone knows the famous depiction of Plato and Aristotle that occupies the center of Raphael's School of Athens. It's worth taking a moment to study the image, as it says a very great deal without a single word, except for the inscriptions on the books each man carries.

Plato stands in the background. Aged, barefooted, with his right hand he points upward, along a vertical line, toward the Heavens, with his left, he holds a copy of his Timaeus. Plato seems to be standing still, but this sense of stillness is belied by his feet, which are in motion. To his left, his pupil Aristotle, a much younger man, appears to move away and ahead of his teacher. The image is of a departure-- but notice, Aristotle's feet are still. In his left hand, he holds a copy of the Nichomachaean Ethics. With his right, he gestures outward and downward. His palm points toward the Earth, but his open hand suggests a horizontal line. The two figures look towards one another, while around them gather all the luminaries of ancient philosophy, science, and art.

This single image captures much about the relationship between the two men-- or, rather, between the philosophical systems that each developed. Of their personal relationship we can only make guesses. Aristotle was the student of Plato for twenty years, during which time he lectured at Plato's Academy. Plato referred to Aristotle as the intellect of the academy; Aristotle eulogized Plato at his funeral. Their relationship during Plato's life appears to have been one of friendship between master and pupil.

After Plato's death, the story changes. Plato was succeeded as head of the Academy by his nephew Speussipus. Following Speussipus, there seems to have been a dispute, with different factions within the academy favoring either Aristotle or Xenocrates. According to at least some accounts, while Aristotle was out of town Xenocrates was made head of the Academy, and following this Aristotle founded his own school. The works of Aristotle's that modern academics believe date from after this time reflect a very different perspective. Many of his works from this period open with an attack on Plato and the Academy, and then go on to contain continuous, tendentious and often tedious attacks throughout the remainder.

The Whole or the Part?

Of course, it's Aristotle's views on reincarnation that concern us here. Fortunately, he left us no doubt at all as to either his position or the reasoning behind it. Put simply, he thought the whole idea was ludicrous. In his commentary On the Soul he tells us why:

It is as absurd as to say that the art of Carpentry could embody itself in flutes; each art must use its tools, each soul its body.

Notice what's being said here. As with Raphael's painting, there is quite a bit contained in a very small space.

If you reason from Aristotle's premises, his point is a good one and it makes perfect sense. No, we cannot imagine Carpentry, as an art, somehow becoming Flutes; just to say so is to utter an absurdity.

Now, consider what is meant by "Carpentry." We use a single word here, and in doing so denominate a single "thing." But that thing consists of a great many, separate processes, including a suite of knowledge, trade schools or apprenticeships in which the knowledge is learned, tools and materials in which the knowledge is applied, and finished products, all transmitted across time. That time is limited, at least in theory; there must have been a time when the art of working with wood to make things like houses and furniture was discovered, and there may be a time in which it is forgotten. But that finite time is different from the lifespans of particular objects, or the length of time it took to produce this house or that chair, or the time that this or that carpenter spent in trade school. John could become a carpenter or not; Sally could make a chair or a house today; Billy could cut his hand with a jigsaw. Carpentry as such is not affected by these particulars. The particulars, then, are akin to the body of the art. In just the same way, you could cut your hair today, or not, or go running and lose five pounds, or eat donuts and gain five pounds. You can go through puberty and double in size, have a baby and double in size again, then go through menopause. Your body will be modified, as the "body" of Carpentry is modified by Sally's chair or Billy's workplace compensation suit. But the "You" of you will remain. It is not reducible to these particulars-- and, yet, it expresses itself through the particulars. It would be as absurd, on this account-- indeed, as grammatically meaningless-- for you to suddenly exist as Billy or Sally as it would for Carpentry to suddenly become Flutes.

This "You" is precisely what Aristotle means by "Soul." It is, as he puts it, the "actuality" of a particular body, or that which is expressing itself through that body. On this account, it is meaningless to even talk about a soul without a body, and doubly meaningless to talk about a soul with a different body. A soul with a different body is a different soul.

The Locus of Being

The difference between Plato and Aristotle is a subject for a very long blog post, and maybe we'll get to that one day. For now, I want to focus on one thing-- but this one thing is a microcosm of the entire divide. That is the approach of each of the two philosophers to ousia.

Ousia is a Greek word which we can translate as "essence," "substance," or-- stretching the point a bit-- as "being." The Platonic account, which we are all familiar with by now, has Ousia as the primary Form out of which all other things emerge. If we can simplify things a bit and simply call it "being," for the Platonists, Being comes first, and all particular beings participate in Being Itself.

Aristotle reverses the situation entirely. For Aristotle, ousia primarily is not being, but this being. Socrates is ousia primarily. "Man," a species of which Socrates is a part, is ousia only secondarily. "Animal," of which "Man" is a part, has a tertiary existence.

On this account, Soul cannot be an eternal principle in which ensouled beings participate. Indeed, Aristotle attacks the very notion of participation, central to Platonic metaphysics, early on in his own Metaphysics. Starting with particulars and rooted in particulars, Aristotle can only interpret the soul as particularity. Indeed, his word for the soul is entelechia, "entelechy," meaning precisely the actuality of this or that particular body.

To Be Continued

There are two different ways to look at Aristotle. He can be seen, on the one hand, as an anti-Platonist-- and, indeed, as the anti-Platonist. Certainly a cursory reading of him bears this out, as, like I said, attacks on Plato are basically constant throughout the entire corpus of his written work.

Given that, it would seem to be somewhat odd that the most important introduction to Aristotle's work, one which endured throughout the Christian Middle Ages, was written by Plotinus's student Porphyry. It would seem even odder that Proclus of Lysias's introduction to philosophy began, not with the reading of Plato, but with a systematic reading of all of the works of Aristotle. Plato is more than human for Proclus, he is divine, and Proclus's masterwork is the Theology of Plato, not the Theology of Aristotle.

So what's going on here?

I'm afraid that's all the time we have for today. Join me tomorrow, when we'll pick up the thread from this point.