Today's post is not fun, but it's something that I felt that I had to say.

The SituationYet another war has broken out, as you're doubtless aware. As of this writing, it's unclear where it's going or when it will end. If we're very fortunate, it will be confined to Gaza, which will be horrible enough. If not, it will spill over into Lebanon and Syria at least, which runs the risk of drawing in the United States and Iran in turn. At that point the powers involved might just well decide that the Ukrainian war and this war are the same war after all, in the same way that everyone decided that the Sino-Japanese War and Anglo-German War were the same war after 1941 or so.

This is not a blog about current events and it's not a blog about politics. As originally conceived, it is a blog about books. And the reason I want to say something about current events is that I'm concerned that some of the books that we have on offer will make very bad guides for the present moment. To say it another way, I believe that we need better bards.

Let me be more specific. There are two stories which I love very much which I think are utterly useless for the present moment, and I worry that since many of my generation were raised on them, they will be floating around in our heads and, whether we realize it or not, guiding our actions. What stories are these?

One is

The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien.

The second is not a book but a movie, though I often imagine that in a thousand years schoolchildren will be forced to read its screenplay the way that modern children read Shakespeare's plays. Of course, I'm talking about Star Wars.

And there is a third, hovering in the background of these and informing both, which we'll get to.

Good and Evil Both of these are war stories, and that's helpful enough to have on hand in a time of war. The trouble is the way that they present war. In both of these stories, as you know, the war is between a Good Side and an Evil Side. The Good Side is all Good, and the Evil Side is all Evil. Moral ambiguity concists only in the possibilty that some characters may move between sides. Once they have done so, however, they then become entirely good or entirely evil as the case may be. Darth Vader, once redeemed, is good; Saruman, once fallen, is evil.

Since the outbreak of war on Saturday, I've seen many, many comments on the war between Hamas and Israel, and every last one of them has framed this conflict in these terms. One side must be good, and equivalent to Aragorn and Luke Skywalker, and the other side must be evil, and equivalent to Sauron and Darth Vader. There are no other possibilities.

Hovering in the background, of course, is that ur-story, the creation myth of the modern world:

The story of World War II.

This is our great modern epic, which has now so consumed the collective imagination that we cast every conflict past or present in its terms. Indeed, as the capacity for reason has diminished-- especially among public intellectuals-- it seems our moral compass consists entirely in determining, in any given situation, which side represents Hitler. New Hitlers are always turning up; in my life, Hitlers have included Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, Slobodan Milosevic, George W. Bush, Saddam Hussein again, Barack Obama, Moammar Qadaffi, Donald Trump, and Vladimir Putin. And, right on cue, today I saw a right-wing commenter on Twitter frame the new war in the Middle East in precisely these terms: "Ask yourself, which side would

Hitler support?"

If you think that these sorts of stories are applicable either to the Russo-Ukrainian War, the war between Israel and Hammas, or any third and nightmarish war which may result from the combination of these two, let me make a suggestion. Find someone you know who supports the opposite side to the one you do, and ask them to make their case to you in detail. Don't say a word; just let them regail you with tales of the atrocities of the Palestinian terorists, the Israeli Defense Forces and settlers, the Russian Army, the Ukrainian Army, the Azov Batallion, on and on and on. I'm not going to do this for you, by the way. If you're a reader who supports the Palestinian Resistance and hates the Zionists, or who supports the state of Israel and hates anti-Semites, don't bother lecturing me in the comments; I'll just ban you. Do the work on your own. Talk to someone who disagrees with you, and ask them why. By the end, you will either understand that you are not the side of the good guys anymore than they are, or you will scream at them to shut up. I'm afraid the second choice is unfortunately common these days, and it's a choice I want to circumvent if I can.

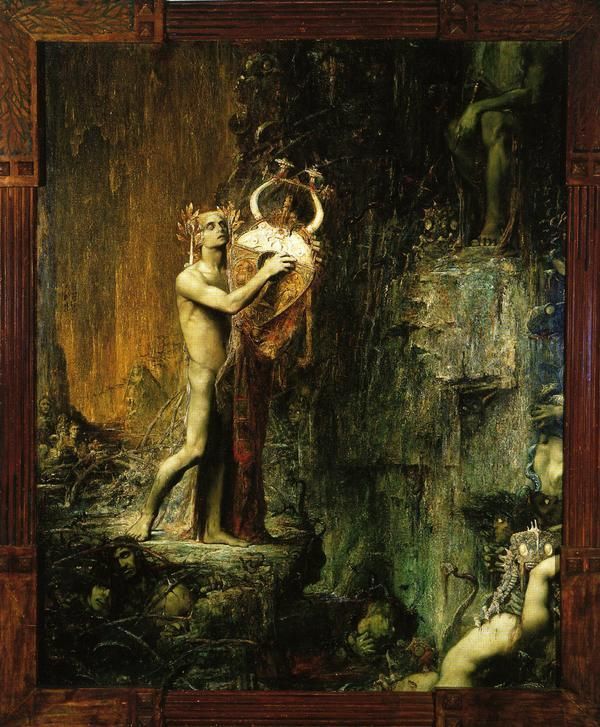

There Is Another Way To Look At WarHumans think in stories as surely as we count with numbers. If we want a different way of thinking-- about any situation-- we need a different story to think with. And so in this case we'll need a war story. The good news is that, as Western people, we are heir to one of the greatest war stories of all time. It's a powerful, dark, difficult and thought provoking story. It's a story with heroes on both sides-- and the heroes are real heroes, the sons of gods. It's a story where men make bad decisions, and good ones, rise to the occasion or are brought low by their own pettiness. It's a story about a war in which the very gods themselves took part, siding with one force or the other as the occasion demanded.

I'm talking, of course, about Homer's

Iliad.

You probably know the story; if not, you should. But let's take a moment anyway and review the facts.

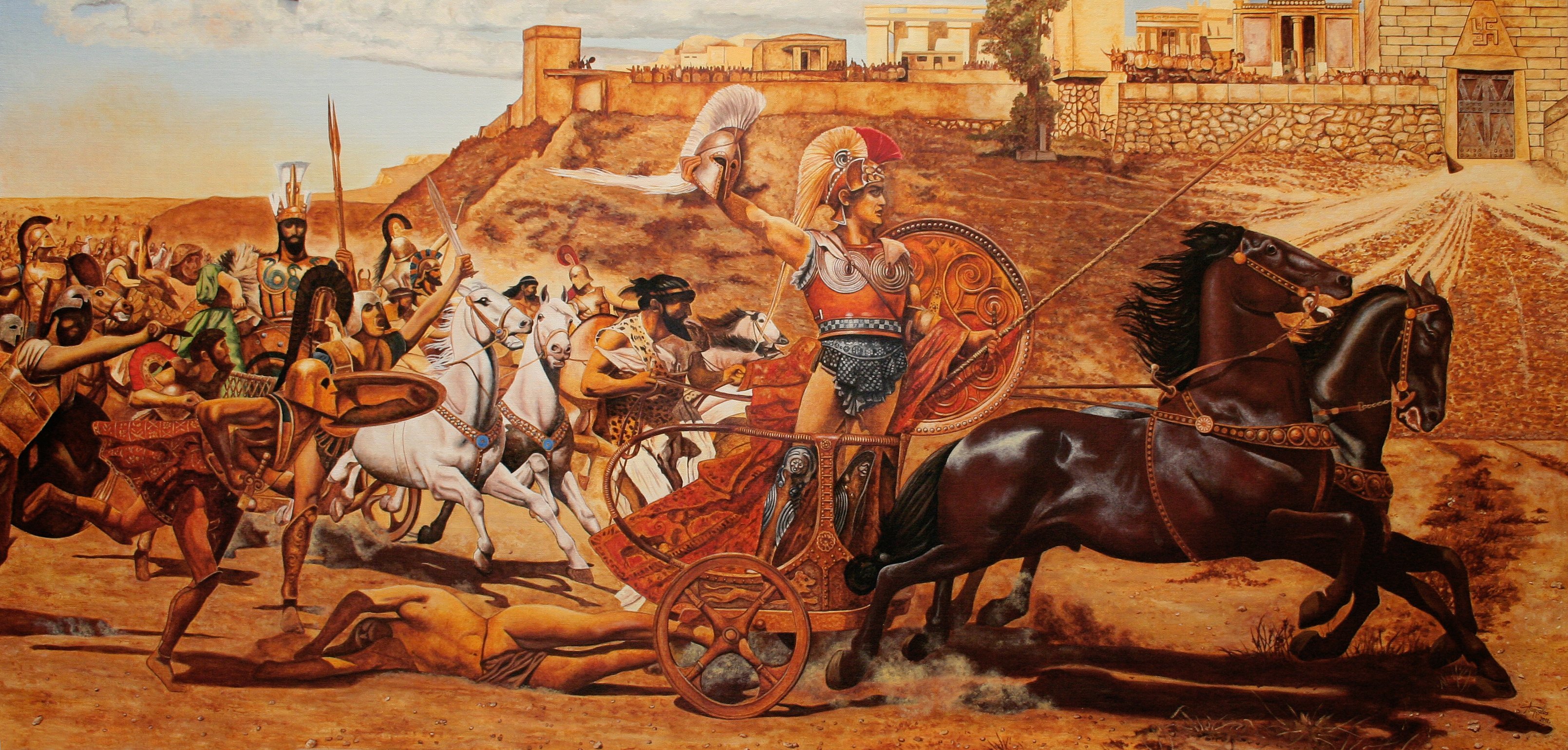

The Iliad begins in the ninth year of the Trojan War. A great coalition of Greek city-states has united against the kingdom of Troy, in order to rescue Helen, the bride of the king of Sparta, taken captive by the Trojan Prince Paris. Over the course of nine years the Greeks have pushed their way through the Trojan lands, and now besiege the sacred city of Illion itself.**

(**You've probably heard that it was a ten year siege of a city called Troy, and that's how I learned it too. But the poem makes continuous references to the Greek armies having conquered many different cities of the Trojans, which implies that Troy was a kingdom or empire and Ilion its capital. Achilles himself tells us that "With my ships I have taken twelve cities, and eleven round about Troy have I stormed with my men by land." And yet everyone claims that the war was a ten year long siege, and that's what you'll see repeated by sources like Wikipedia. No, I don't know why.)

Over the course of the poem, the Greeks and the Trojans fight back and forth, and neither side is able to defeat the other. The gods themselves intervene. Poseidon and Hera and Athena fight alongside the Greeks; Zeus and Aphrodite and Ares stand with the Trojans. The heroes contest with one another. Aeneas, the Trojan son of Aphrodite, contends with Diomedes, and is only saved from death by the intervention of his mother and Apollo. Patroclus, companion of Achilles, kills Sarpedon the son of Zeus. Hector, great leader of the Trojans, kills Patroclus in his turn.

Patroclus is the companion of Achilles, greatest of the Greek warriors, and up until now Achilles has behaved like a sulking child. At the beginning of the story his captive bride is taken away by Agamemnon, and Achilles withdraws from the fighting, refusing to intervene to save the Greeks from certain defeat. When he finally, grudgingly, allows his men to return to the fight he still refuses to go himself, and Patroclus is only killed because he was wearing Achilles' armor and mistaken for Achilles himself. Now Achilles, filled with rage, sacrifices a number of Trojan soldiers on Patroclus's funeral pire and marches into battle, girt with new arms and armor made by Hephaestos. Armed by the gods, he kills Hector before the walls of the city.

Thorughout the story, as I've said, Achilles has behaved like a spoiled brat, while Hector has been brave and sympathetic, an honorable leader of men. And now, not even Hector's death is enough to appease Achilles. He mutilates Hector's body and drags it behind his chariot around the walls of Troy. Oh, and he sacrifices a number of Trojan warriors on the funeral pire of Patroclus to boot. It's still not enough; like a child having a tantrum, he can't calm himself, and he falls to brooding, periodically taking a break to drag poor, dead Hector around some more.

At the very last, Priam, Hector's aged father, comes to Achilles to beg for the body of his son to be returned to him. And now, after 24 books of sulking and murder, Achilles relents. He invites the old man to his tent, and together they drink, and eat, and tell stories. They weep for the dead on both sides. Achilles returns Hector's body with a promise that the Greeks will obey a truce for twelve days, so that Priam will have time to bury his son.

Here is how the story ends:

Forthwith they yoked their oxen and mules and gathered together before the city. Nine days long did they bring in great heaps of wood, and on the morning of the tenth day with many tears they took brave Hector forth, laid his dead body upon the summit of the pile, and set the fire thereto. Then when the child of Morning, rosy-fingered Dawn, appeared on the eleventh day, the people again assembled, round the pyre of mighty Hector. When they were got together, they first quenched the fire with wine wherever it was burning, and then his brothers and comrades with many a bitter tear gathered his white bones, wrapped them in soft robes of purple, and laid them in a golden urn, which they placed in a grave and covered over with large stones set close together. Then they built a barrow hurriedly over it keeping guard on every side lest the Achaeans should attack them before they had finished. When they had heaped up the barrow they went back again into the city, and being well assembled they held high feast in the house of Priam their king.

Thus, then, did they celebrate the funeral of Hector, breaker of horses.

The End.

The

Iliad is a very difficult book for modern readers. Its ending is not triumphant. The Death Star does not explode. The ring is not cast into the fire. Hitler does not shoot himself in a bunker. It ends in the funeral of a good man, with more war still to be fought. It is a hard story, a bitter and a sad story. And in that it is more thoughtful than every World War II remake that the past 80 years has given us-- very much including our fanciful and self-aggrandizing account of the war itself.

In the

Iliad, there isn't a right side and a wrong side. The war began long before the text itself, with Paris, prince of Troy, carrying off Helen, wife of the Spartan King Menelaus. But Paris was promised Helen by Aphrodite, a goddess, and some sources claim she went willingly; in any case Paris himself is no mere robber. He is also known as Alexandros, "defender of men," a name that he was given for heroic deeds in his childhood. And the Greeks are not the Star Wars rebels or Tolkien's elves. Agamemnon, their supreme commander, sacrificed his own daughter to Artemis to ensure victory. And victory he was given, but for his deeds the gods allowed him to be murdered by his own wife upon his return to Argos. There are heroes on both sides, villains on both sides, gods on both sides.

It is a story for our time, and it is the story of our wars.

An Hour For MenLet me tell you a hard truth. And for this I'm going to have to ask that the children and the faint of heart leave the room; this isn't for you.

Star Wars and

The Lord of the Rings are stories for children. Moreover, the story on which they are based, the tale of our heroic struggle against evil in World War II, is a lie. The Second World War was a war like other wars. The Nazis were guilty of monstrous war crimes. And so was our great ally, the Soviet Union, a monstrous prison-state which would have been destroyed if not for American aid. And so were we. At Dresden and Hamburg, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki we murdered hundreds of thousands of people, most of them civilians. World War II was a war like other wars; we celebrate it because our side happened to win.

Now, there is an easy way to misunderstand what I'm saying, and so I'm going to address it now. My point is not that America should not have been involved World War II, or that we were "just as bad" as the Nazis. My point is that there were evil deeds on both sides, and there were good men on both sides. Again, we like to use the word "Nazi" as a stand-in for "evil," but it's easy to see that this isn't so. Imagine that you are a German of military age. The year is 1944. To the east, the Red Army is rolling through Poland, bringing murder, rape, and mass enslavement. To the West, the Americans and their British allies are advancing through France, and the New York Times has just published the Morgenthau Plan to reduce Germany to an agrarian society after the war. For years British and American planes have been raiding German cities, killing indiscriminately. You loathe Hitler, and you believe the rumors you've heard about the camps at Dachau, Auschwitz and elsewhere. But everyone knows what the Soviets have done at places like

Katyn Forest, and your cousin who survived Dresden has told you what the Americans are capable of. What do you do?

In real life, evil doesn't dress up in a black helmet, and good doesn't wear white wizard robes. There are no good or evil people. There are only good or evil actions.

And--

This is the really hard part--

In real life, unlike in fantasy stories, two people can both choose good, and still end up on opposite sides of a conflict. They can even end up killing each other. This is what it means to say that "The gods fought on both sides" of a war. This, actually, is why polytheism is more realistic than monotheism, especially as regards life on Earth.

A Thought ExperimentLet's illustrate the point.

Suppose a family member, a member of your household, got into a conflict with a neighbor. How it began doesn't matter. Let's just say that it became, over the course of months, one of those intractible human conflicts marked by tit for tat retaliations, with each side blaming the other. Let's say that when you tried to talk to your family member-- let's say it's your son-- about the matter, it was clear that both sides were at fault, and had done terrible things, but that he had started it. Maybe the neighbor was another boy, and your son called called him a name, and the other boy hit him, and your boy retaliated by getting his friends together to beat up the other boy. On and on and on.

It's a terrible situation, right? And a situation all too common among human beings. The right thing to do is to have both sides sit down, admit their own part in the conflict, apologize for their misdeeds and forgive the other's. That's what should happen.

But-- Uh oh.

It looks like the neighbor kid's snapped. The beating he took from your son and his friends was the last straw. Now he's coming over to your house with a knife.

Your son is in the back yard. You yell, but he doesn't hear you. There's the neighbor kid. He runs into the backyard and knocks your son down. There he is, holding the knife, about to kill your son. But now, as luck has it, you have a gun in your hand, and a clear shot.

What do you do?

There's no good side in the conflict, and your son started it in any case. You can imagine what drove the neighbor kid to react this way-- imagine his fear and humiliation as your son and his friends beat him into the ground behind the school. Now you have a chance to shoot and kill him on top of it, and become a murderer. Would you do it anyway?

I would, and I'll bet you would too.

Why? Because the other kid is evil? Because he's no better than a nasty orc or a Stormtrooper or-- worst of all-- A

Nazi?

Grow up.

I'd shoot him and you'd shoot him because it would be the right thing to do. It would be the right thing to do not because he is evil, but

in spite of the fact that he is not evil. In the final analysis, it would be the right thing because duty to family is a part of the virtue of piety, and piety is a part of Justice.

It's a horrible thing to think about. No one wants to face a situation like that. But in this real world, situations like this are far more common than fights with orcs or goblins or stormtroopers or "Nazis."

Why Talk About ThisIf we are fortunate, and pray to God that we will be, the latest conflict in the Middle East will be resolved quickly. But there's a chance that it won't be. If so, many of us are going to have to make choices. They are going to be hard choices.

What I want is for us all to make them with our eyes open, like men. If we have to choose sides, let us each choose the right side.

The right side is not the side of the elves, or the angels. The right side is not the side of whoever is fighting "Nazis." There are no Nazis. There never really were, in the mythical sense. There are only other human beings, all a mix of good and evil, some more good on the balance, some more evil.

The right side is the one which Justice demands you support. Not me, not your cousin, not your favorite YouTuber: You. Justice is a virtue, and it has a clear definition: It consists entirely in right relationships. Now loyalty or Fidelity is a component of Justice, and each of us has groups which rightly demand our loyalty. In order to act justly, we must decide which groups those are, and act accordingly.

In the

Iliad, the Greek kings join Menelaeus and Agamemnon because that is what Justice demands of them. The Trojans also had allies; the Amazons fought alongside them, and so (after the events of the Iliad) did the Aethiopians. When Memnon, king of the Aethiopians, obeyed the summons to war, he obeyed the command of Justice; when Achilles slew Memnon as he had slain Hector, he too obeyed the commands of Justice. It's not cinematic, it's not satisfying, it doesn't make us feel better about ourselves. But it's real.

Obedite mandata Iusticiae-- "Obey the commands of Justice." Let this be our slogan, and not "Kill the Nazis." We'll likely feel worse about ourselves, and worse about whatever killing we do or our side does. And I'd suggest that that's a very good thing.